When conceptualizing our edition of Master and Commander, I knew that the covers of the lettered edition of 27 copies called for something special… something that would create a tangible link to the nautical world of Jack Aubrey. Wood from HMS Victory would be that magical element.

Two Millenia of Wood as Book Covers

Wood covers have been a part of the codex – a book made from a stack of pages bound at one edge – since inception. The precious papyrus, vellum or paper on which words were painstakingly written by hand needed protection in the form of strong, flat covers. Although sheets of metal and other materials were sometimes used, wood boards were, by far, the most common choice for more than 1500 years. Indeed, the very word “codex” is derived from the Latin word caudex, meaning “trunk of tree” or “piece of wood.”

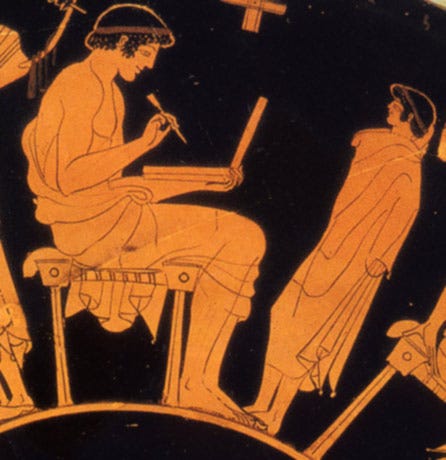

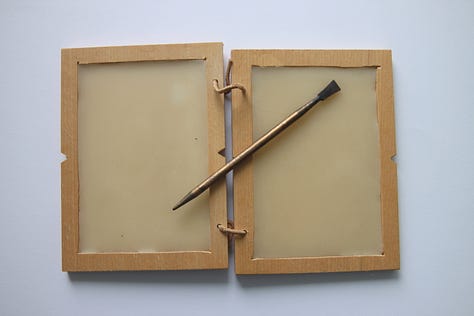

The precursor to the codex was the Roman tablet in which two wax-covered pieces of wood were tied together and used for temporary writings (e.g., note-taking, lists, etc.) for hundreds of years.

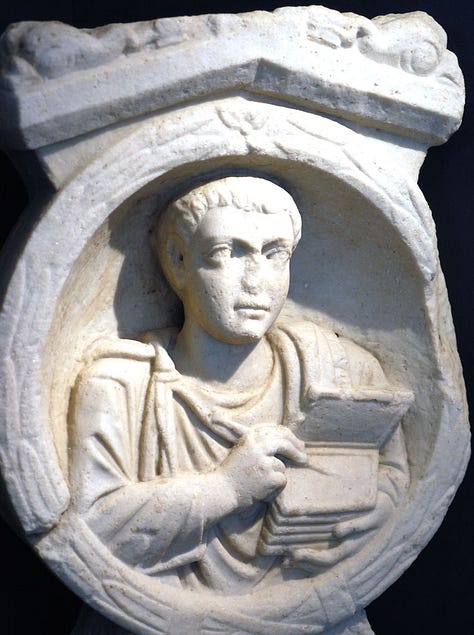

By the first century C.E., the Roman poet Martial “made the rare decision to republish [Epigrams] in codex, a format hardly ever used for literature.” Martial contrasted his codex with the vastly more common roll or scroll, advertising his edition as a “handy format that can be held in one hand and brought along on a journey.” As Philip Boserup-Lemire wrote in a 2014 article in Classica et Mediaevalia, a Danish journal of Philology and History:

Martial was a bibliophile at heart, with a keen interest in the anatomy of the book; and although he introduces his codex edition as a user-friendly pocketbook, pointing out its advantages over the roll, I suggest that this edition was an attempt to bring a new format of the book to the literary world, not primarily for the sake of practicality, but to create an elegant interplay between the text and the physical book.

All bibliophiles owe Martial a debt of gratitude for popularizing what we have come to know as the “book.” And, although no period copy of his Epigrams has survived, wood covers most certainly protected the valuable pages of the book.

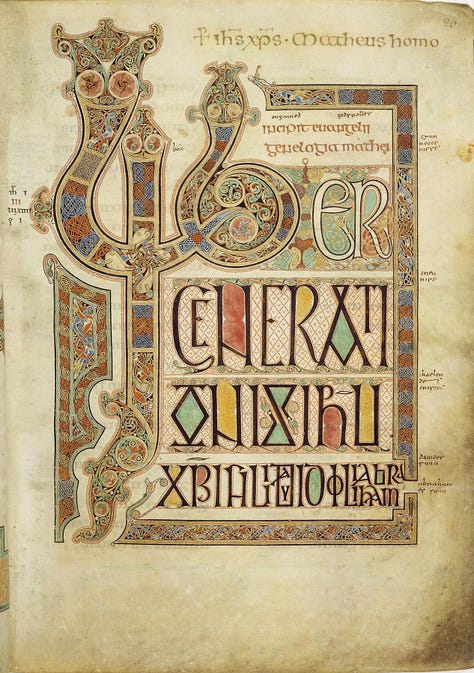

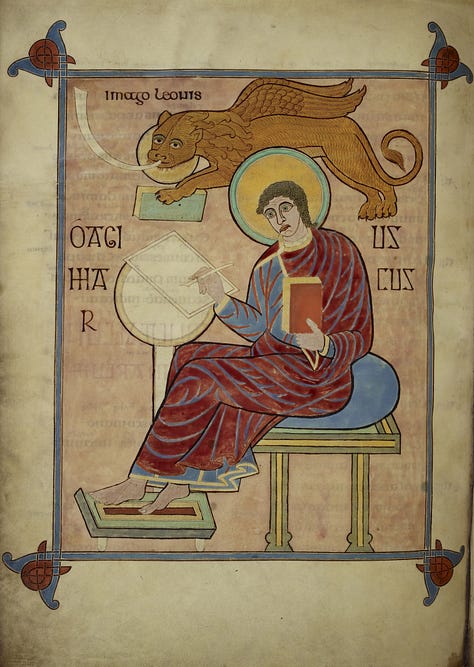

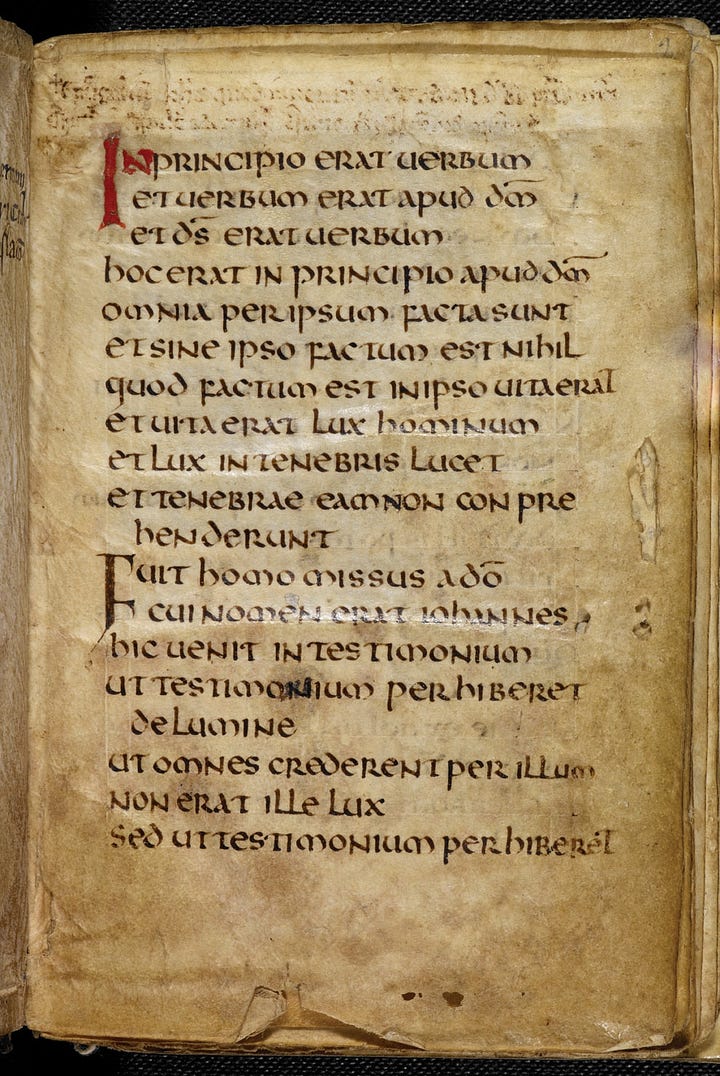

Despite the decline of Roman political control throughout Europe, wooden-covered codices remained. A small island just off the coast of Northumberland, Lindisfarne was a center of Celtic Christianity from the 6th century. It was there that a small bound copy of the Gospel of John was placed in the coffin of Cuthbert of Lindisfarne (634-687) a few years after his death. The casket rested peacefully for nearly 200 years, a silent witness to the creation, in honor of St. Cuthbert, of the greatest work of Hiberno-Saxon literature, the Lindisfarne Gospels (c. 715).

The peace of the monastery was shattered when Vikings arrived at the monastery in 875. The monks fled, carrying the coffin of the St. Cuthbert (book still inside) with them. After seven years of temporary homes, the saint’s body remained in Chester-le-Street for over a century, before finding a final resting place in Durham Cathedral in 999. There, during a reburial in 1104, the book was removed from the coffin and kept as a relic. Important visitors were allowed to wear it in a leather bag around their necks.

The book remained in Durham until the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII between 1536 and 1541 when it – like so many of the relics and wealth of the church – made its way into private hands. It passed through the libraries of an Oxford mathematician, the Earl of Litchfield, and a Catholic priest serving as chaplain to the Earl of Shrewsbury. Finally, in 1769, the priest gave the small book to the Jesuit college at Liege. Confronted by the chaos of the French Revolution, the college moved back to England, becoming Stonyhurst College, a Jesuit school in Lancashire where the book remained until 1979.

After three decades on loan to the British Library, in 2012 it was purchased for their permanent collection for £9 million. The British Library calls the St. Cuthbert Gospel "the earliest surviving intact European book and one of the world's most significant books."

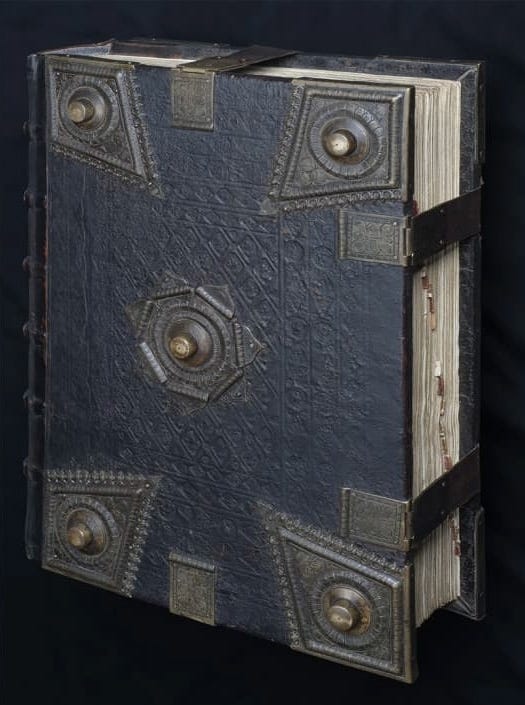

The small volume (just 5.4” x 3.6”) is a magnificent example of early Celtic Christian design. Rather than the complex illumination of slightly later texts (e.g., the Lindisfarne Gospels), its pages feature simple calligraphic perfection on vellum. In its simplicity, it stands in contrast to early medieval “treasure bindings” whose pages were highly illuminated and whose covers often used precious metals or even ivory for the book’s cover structure.

In a 2015 CT scan of the book, the grain pattern of the wood and underlying decorative elements are clearly revealed. The raised design was created by attaching cord and other materials to the wooden board. It was then covered in sumac-tanned goatskin leather from sub-Saharan Africa. The fine debossed designs were added to the completed binding and filled with two yellow hues – made from orpiment, a crystal sourced from Asia Minor – and blue made from woad indigo. Miraculously, the leather has survived in near pristine condition for well over 1400 years. Although Cuthbert’s body may not have been incorrupt, his book certainly was!

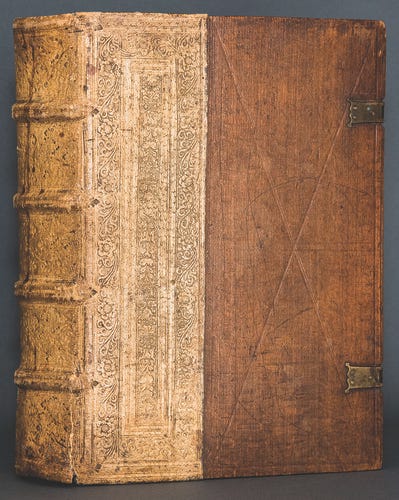

The St. Cuthbert Gospel represents the first known use of wood panels in the creation of the codex in post-Roman Europe, a trend that would last for nearly 1000 years. Countless are the medieval and Renaissance texts that have been protected by wood boards. Although the variety of wood varied from place to place, quartersawn oak was popular for its strength, dimensional stability, and beauty.

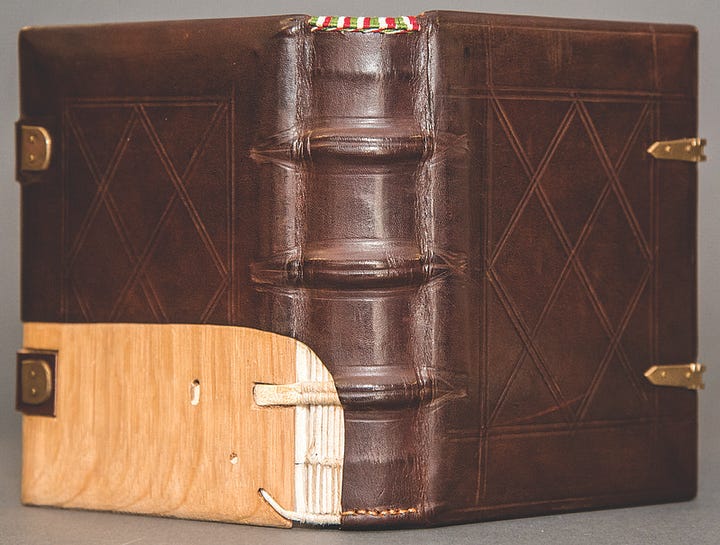

The process of creating such a stunning medieval oak binding is detailed with remarkable artistry and craftsmanship by Dennis Pike of Four Keys Book Arts in Canada.

The use of wood for book covers did not only serve to protect the pages from damage. It also helps them hold their shape, especially before paper replaced vellum as the standard material for carrying text. From personal experience, I know vellum can be a beast to work with. The slightest change in environment – think moving from a warm sunny Spring afternoon to an early evening thunderstorm – can wreak havoc on it. It develops ripples and becomes wavy… it wants to curl and bend. This is one of the reasons that so many medieval bindings used clasps to hold books closed. Not only did such fasteners keep the covers from splaying outward under the pressure of the changing vellum, but the covers kept the pages pressed flat(ter) by applying pressure to the book block. Once paper replaced vellum, the use of such hardware all but disappeared from books.

Even Gutenberg’s revolutionary creation of moveable type had very little impact on the use of wood as a cover material.

By the 17th century, however, the woodlands of England had been devastated. For over 4000 years, woodlands had been cleared for agriculture, building materials, and fuel. In 1086, the Domesday Book estimated that 15% of England’s land was wooded, a figure that was halved by 1700. This decline was accelerated by the expansion of navies and global shipping in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, with more than 2000 oak trees needed to build an average ship, and as many as 6000 needed to build a ship of the line such as HMS Victory. By the start of the 20th century, less than 5% of English land remained wooded.

Although one of the least critical impacts, this decline was felt by those binding books in both England and the Continent (which had seen similar declines in woodlands). Fewer quality boards were available at exactly the same time that the printed book emerged and demand increased. To replace wood, sheets of very thick, rigid, and heavy handmade paper replaced wood for book covers. Such historic “binders board” is still produced for Colophon Book Arts today.

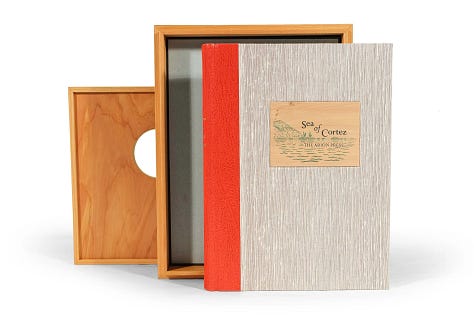

By the rise of the Industrial Revolution and the mechanization of book production, wood was never used in the commercial production of books. Although a few artisan binders and fine presses continued to employ it in fine bindings, by the time that our special edition of Master and Commander was being conceived, such use of wood was rare indeed.

HMS Victory Wood Covers

For the teak covers of my HMS Victory Edition of Master and Commander, I wanted to let the wood tell the story. I did not want it to feel like a medieval book. I especially did not want thick wood panels that, even with chamfered edges, would simply feel overwhelming and out of balance for the edition. Although wood covers had fallen out of favor by 1800, I wanted the edition to still convey the feel of a book on Dr. Maturin’s shelves.

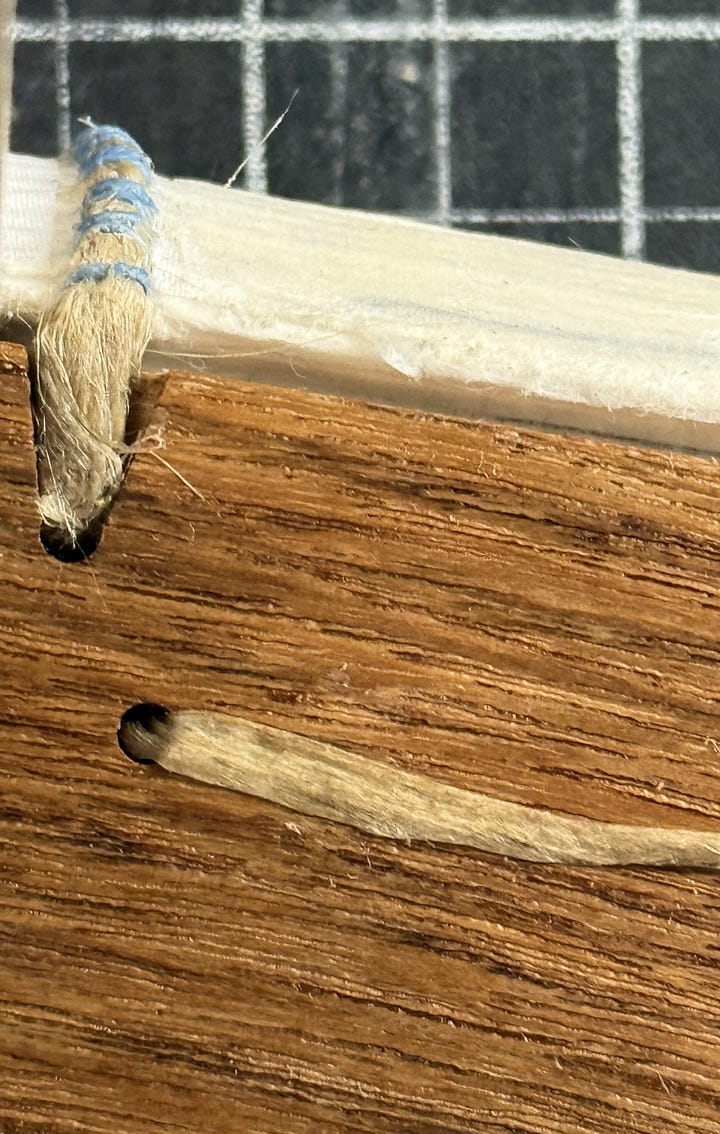

I have previously shared the joys and tribulations of securing the wood from HMS Victory and getting it milled to my specifications. At long last, they are completed and ready for use in the final binding. Each board has been milled to size. Holes and slots for the cords have been carefully machined. A very narrow groove in which the edge of the leather will rest has been added. Finally, the logo of HMS Victory has been engraved inside the front cover.

Now, with the finished boards in the studio, I have begun threading them onto the cords. In keeping with the nautical theme, I will be inserting small brass pins into the pre-drilled holes to keep the cords right and tight.

Once I have finished attaching the covers, all that remains is covering the spine with leather, adhering the leather hinge between the cover and the book block, and attaching the maps (yes, plural… but that is for a future update). Nearly there!

Production Update

All 100 paid copies of the Anchor Edition have been posted to backers, including a few with special order boxes. All that remains is to complete the final steps of the 27 copies of the HMS Victory Edition and a very few special order copies. Spending the early summer in the studio finishing up this massive undertaking is a delight, Look for more updates soon.

Such a niche topic! First article I read about this :)

Thank you for giving attention to such a underestimated topic!

A wonderfully informative write up. Thank you.