Our HMS Polychrest Broadside and Generosity

The Making of "Master and Commander" – Chapter Three

The past three weeks have been tremendously heartening. Like so many people, I often give in to despair in the face of the world’s travails. I also had my doubts about whether there was a community of book lovers – especially lovers of the work of Patrick O’Brian – large enough (and crazy enough!) to support our private press edition of Master and Commander. Yet, I have been buoyed up by the generosity of many strangers – nay, new friends – since announcing our plans. Certainly the overwhelmingly positive support for the project by so many people on Kickstarter was a delight, as were the many private messages of support we received. Beyond that, however, the entire process of planning this edition has been filled with kindness and generosity from individuals far and wide. The Patrick O’Brian Literary Estate… the publishers of Mr. O’Brian’s work – W.W. Norton in the U.S. and HarperCollins in the Commonwealth… the National Museum of the Royal Navy… artists and craftspeople from across the globe… and others in the private press community – particularly Mr. Griffin Gonzales of Portland’s wonderful No Reply Press. All have exhibited true kindness and generosity in making this edition possible. I am truly grateful.

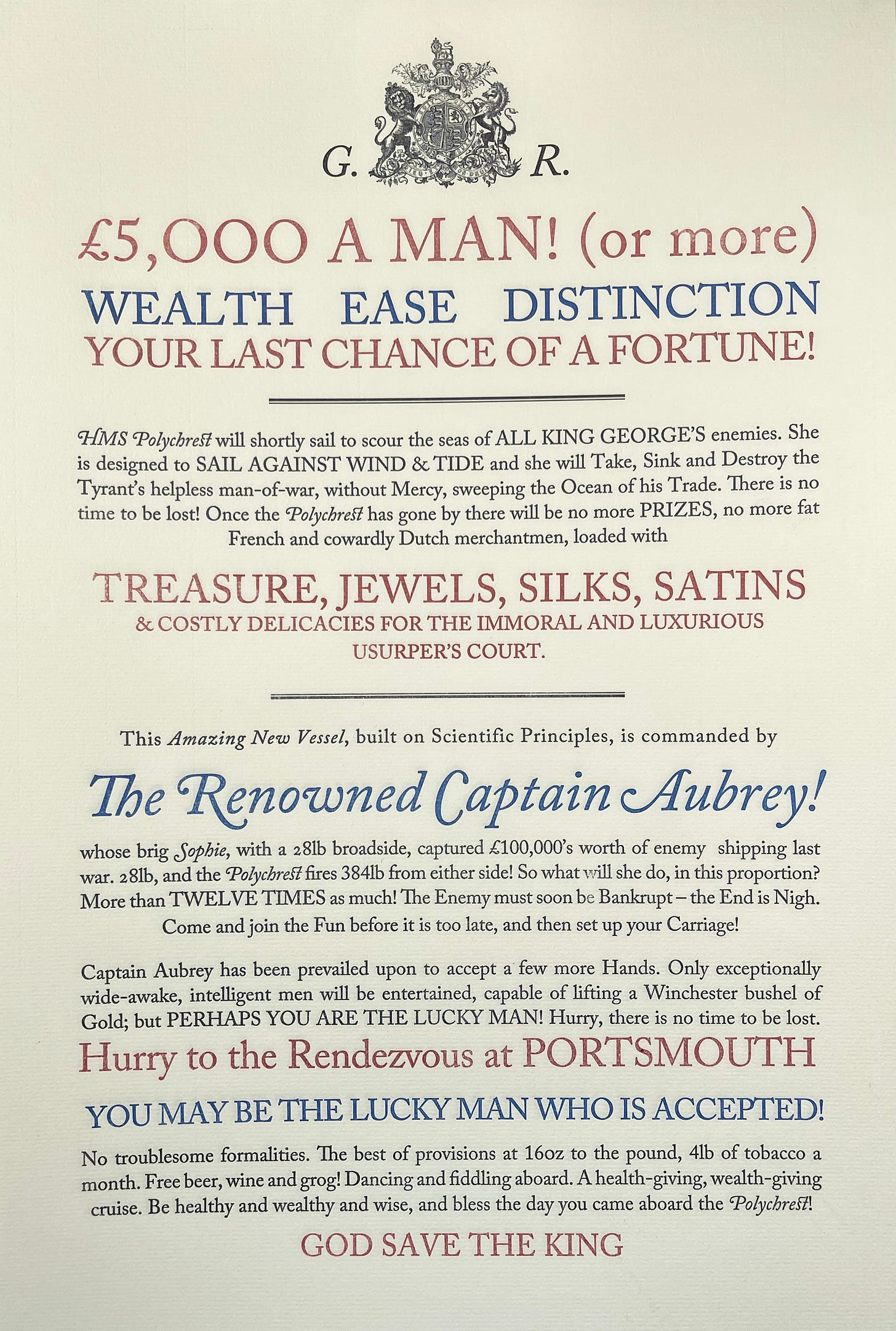

Recently, I continued to see this generosity of spirit and eagerness to support our work from two particular individuals who contacted me about our HMS Polychrest broadside. As part of our Kickstarter campaign, we are offering a three-color letterpress poster – our version of the one Mr. Scriven writes for Jack in Post Captain. Their correspondence brought me much joy, some of which I hope to share with you here.

But I get ahead of myself. Let me begin at the beginning by providing a brief context for our broadside.

The “Other Kind” of Broadside

As every reader of the Aubrey/Maturin series knows, a broadside is the coordinated firing of cannon on one side of a warship. The flash of the powder. The roar of the guns. The acrid smoke. And the enemy striking her colours!

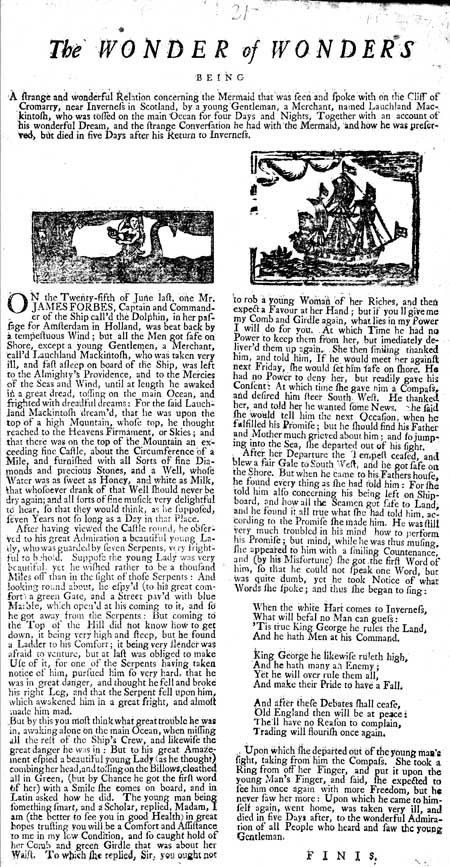

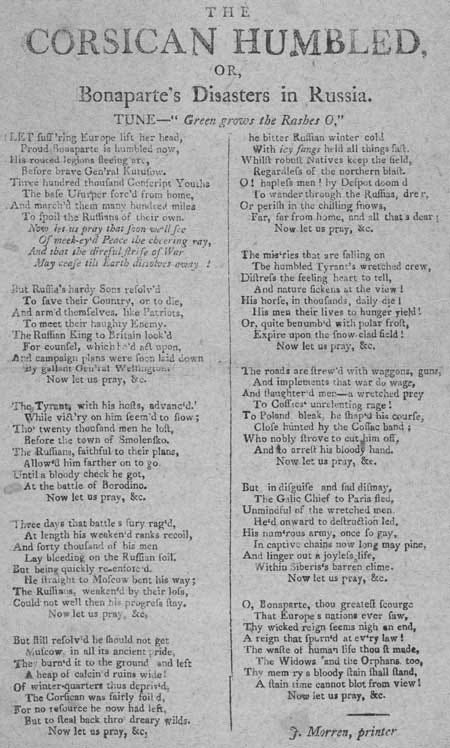

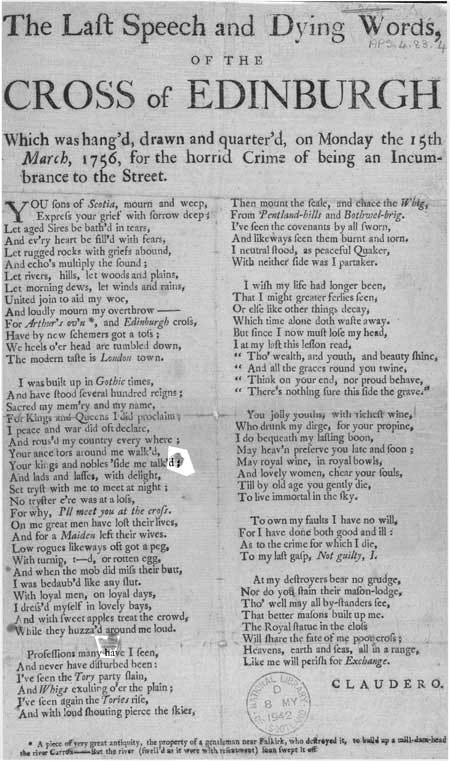

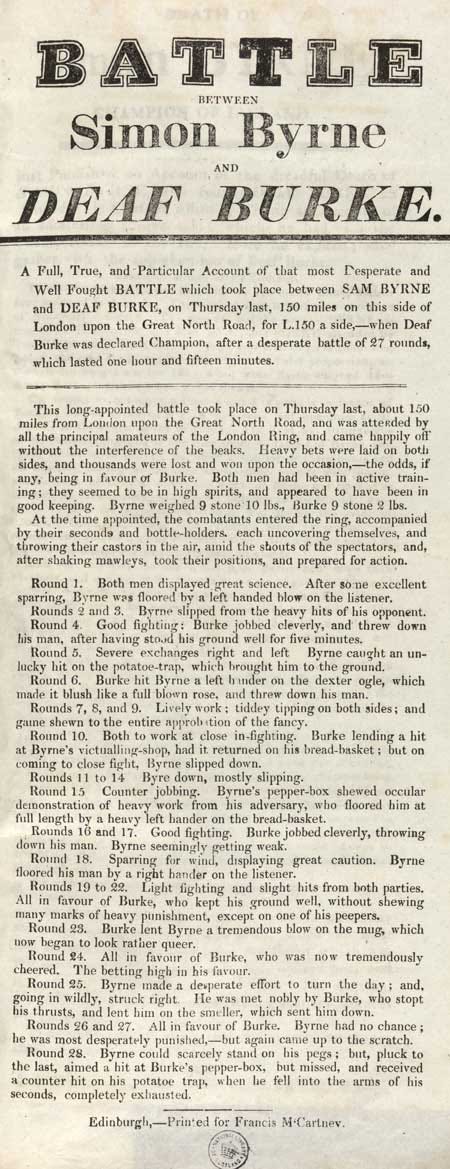

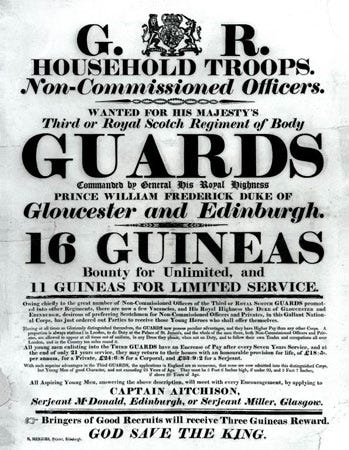

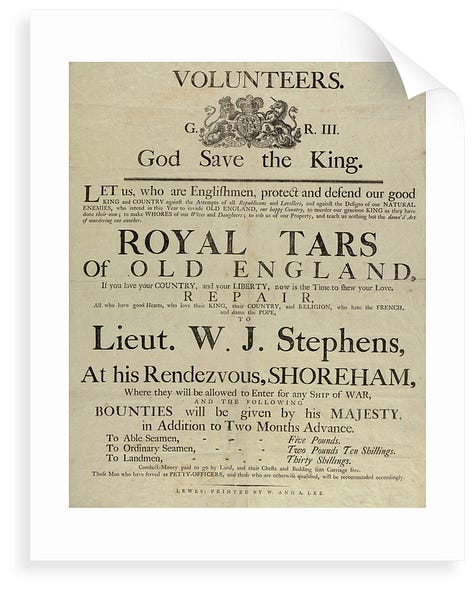

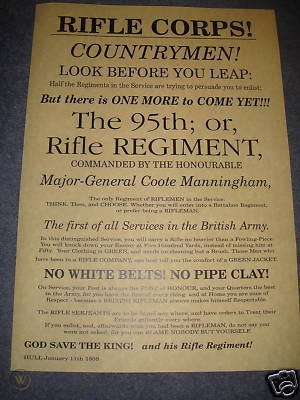

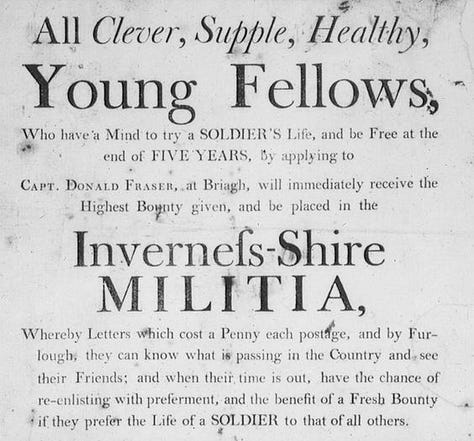

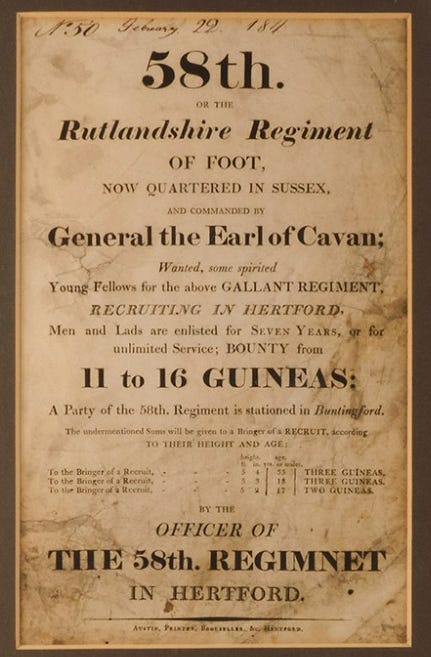

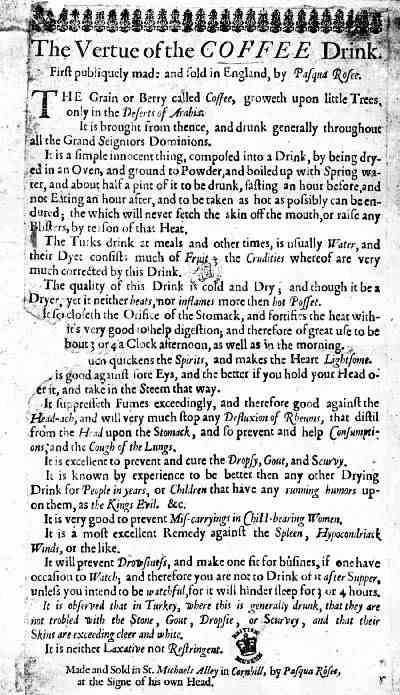

Of course, in our case, we are talking about the “other kind” of broadside. From the earliest days of the printing press in the mid-15th century until the industrialization of printing in the mid-19th century, the broadside was a one-sided poster used to convey information publicly. Royal decrees, news of the day, political commentary, ballads, advertisements, and more were posted. Although they would eventually be replaced by the newspaper and inexpensive books on cheap wood-based paper (hence “pulp” novels), broadsides were the main form of public communication for four-hundred years across Europe. “The Word on the Street” – a website curated by the National Library of Scotland – has digitized over 1,800 of their collection of over 250,000 such broadsides. Here are just a few examples:

A personal favorite – one which I plan to produce in facsimile form in the future – is a 1642 advertisement for Pasqua Rosee’s coffee house, the first of its kind in London. Extolling “The Vertue of the COFFEE Drink” it sets forth the many benefits of my favorite brewed beverage. Although I cannot attest to coffee’s benefits for the spleen, running humors, scurvy or hypocondriack winds, I can, indeed testify that “it will prevent Drowsiness, and make one fit for busines [sic].” Indeed, without it, our edition of Master and Commander might never come to be!

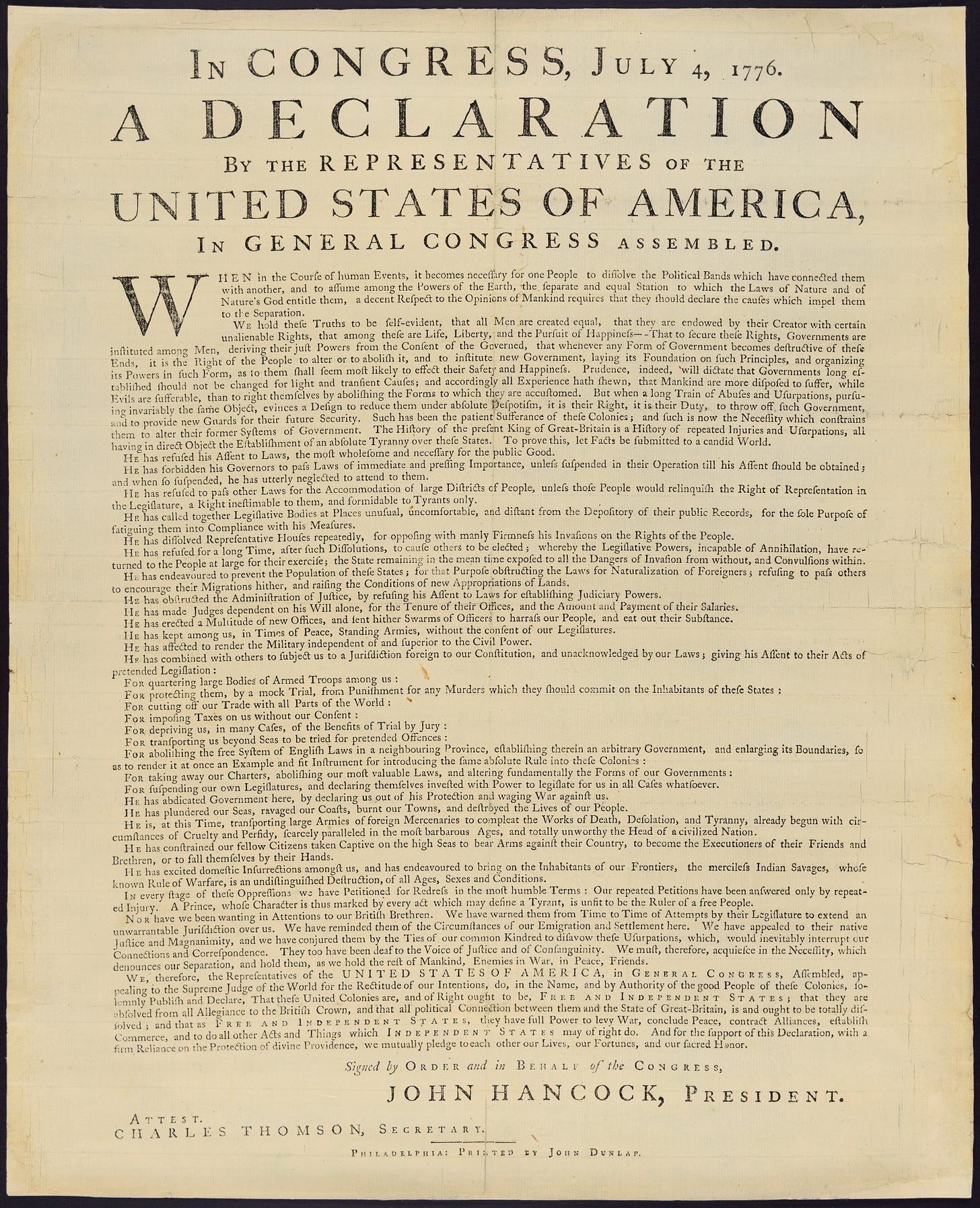

Perhaps the most famous broadside – at least on this side of the Atlantic – is the Dunlop Broadside printed by Philadelphia printer John Dunlop on the night of July 4, 1776.

“There is evidence it was done quickly, and in excitement—watermarks are reversed, some copies look as if they were folded before the ink could dry and bits of punctuation move around from one copy to another,” according to Ted Widmer, author of Ark of the Liberties: America and the World. “It is romantic to think that Benjamin Franklin, the greatest printer of his day, was there in Dunlap's shop to supervise, and that Jefferson, the nervous author, was also close at hand.” John Adams later wrote, “We were all in haste.” The Dunlap broadsides were sent across the new United States over the next two days, including to Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, George Washington, who directed that the Declaration be read to the troops on July 9. Another copy was sent to England. (Wikipedia)

Military Recruiting Broadsides

It is no surprise, then, that broadsides became a tool of recruiting soldiers and sailors during the Napoleonic wars. They did not simply call upon duty, they promised wealth, honor, comfort, tobacco and drink, and more.

It is within this tradition that, in Post Captain, Jack Aubrey decides to print a poster to recruit hands for his new command, HMS Polchrest.

‘[Mr Scriven] is an eminent hand at writing, is he not? Pamphlets and such? I have tried dashing off a poster – even three or four volunteers would be worth their weight in gold – but I have had no time, and anyhow it don’t seem to answer. Look.’ He brought some papers out of his pocket.

‘Well,’ said Stephen, reading, ‘No: perhaps it don’t.’ He rang the bell and bade the man ask Mr Scriven to walk up. ‘Mr Scriven,’ he said, ‘be so good as to look at these – you see the problem – and to draft a sheet to the purpose. There is paper and ink on the table over there.’

Scriven withdrew to the window, reading, noting and grunting to himself…

‘Sir,’ said Mr Scriven, ‘may I show you my attempt?’

Available for a limited time and only through our Kickstarter campaign, we plan to print our final version next week and send it to backers shortly thereafter.

Having made public my intention to offer this HMS Polychrest broadside, I was on the receiving end of notes from two kind and generous gentlemen. Each, in very different ways, brought joy and delight – one by helping us improve the historical accuracy of our broadside, the other by contextualizing it within the publishing history of Patrick O’Brian’s work.

Royal Arms and Getting the Details Right

A couple of weeks ago, Mr. Patrick Crocco of the Royal Heraldry Society of Canada contacted me with an offer of aid in making our broadside more historically accurate.

I don't want to be a nit picker (as the good Doctor would say: “let us not be pedantic, for all love”) but I think the rendition of the Royal Arms at the head of your broadside/broadsheet may be inaccurate as it represents the arms as they were from the start of Queen Victoria's reign (1837). Those of King George III post 1801 would have been charged with an inescutcheon surmounted by the electoral bonnet… From a heraldic perspective, it's like using a 50 star US flag for a WW II film.

Nit picker and pedantic? Quite the contrary, my dear Mr. Crocco! Although I have to admit to being out of my depth in regard to “an inescutcheon surmounted by the electoral bonnet,” I had nothing to fear. Following this gentle correction, Mr. Crocco proceeded to provide me with several sources for the correct version of the Royal Arms, complete with references.

Mr. Crocco’s kindness means that our broadside does not have 50 stars (to mix references). For that, I am grateful. The design has been corrected and new printing plates for our final version of the HMS Polychrest broadside are in production.

An Original Master and Commander Broadside

In yet another act of generosity, I awoke a few days ago to a kind email from Mr. Viktor Wynd – pataphysicist, writer, curator, collector, dilettante, naturalist, and antiquarian. Not only is he proprietor of the remarkable Viktor Wynd Museum of Curiosities, Fine Art & Natural History in London, but he happens to be the grandson of Patrick O’Brian. Indeed, Mr. Wynd was one of the first people with whom I was in touch when seeking permissions for our new edition of Master and Commander, and his generous support was instrumental in moving the project forward.

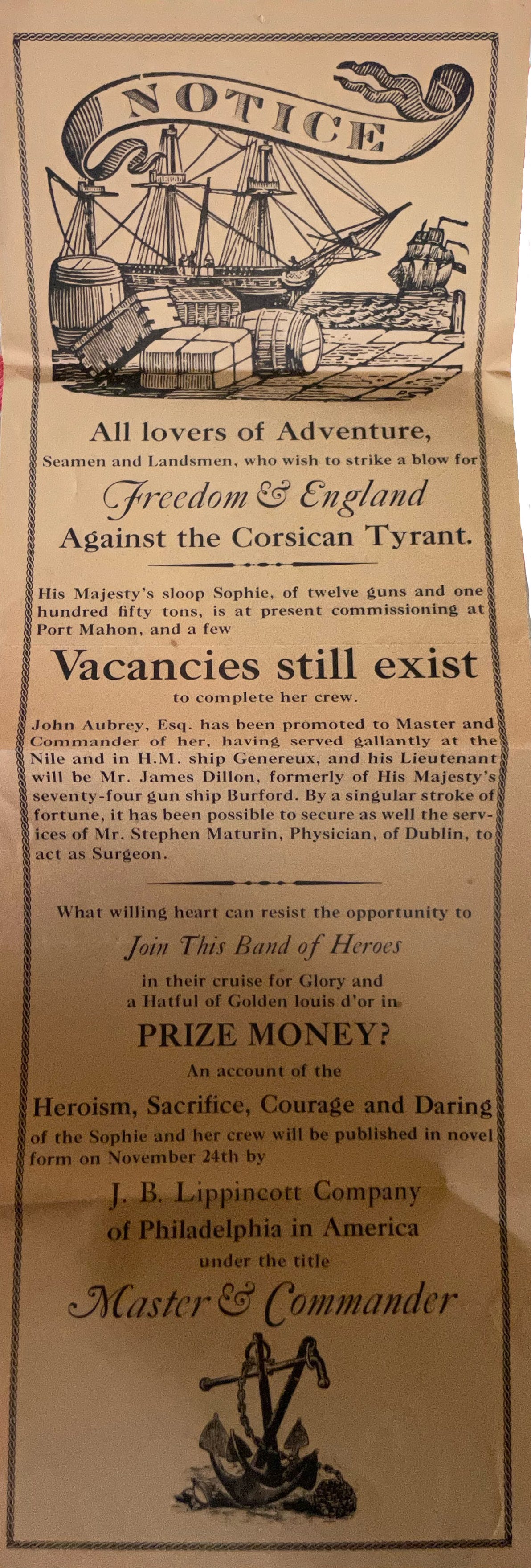

Expressing his enjoyment of our HMS Polychrest broadside, Mr. Wynd wondered if I was aware of a much earlier broadside. It turns out that Mr. Wynd’s collection includes an advertisement printed in 1969 by the J.B. Lippincott publishing company to promote the upcoming release of a new novel… Master and Commander. I certainly was not aware of it, my dear sir! “I've never seen another copy or read it referred to,” wrote Mr. Wynd. Given the nature of such ephemera, I would not be surprised if this is the only copy still in existence. With Mr. Wynd’s blessing, I am pleased to share it with you here.

Although this promotional broadside failed to demonstrate the flair of Mr. Scriven’s, it certainly mirrors the recruiting broadsides of the Georgian era. Moreover, it places the Ampersand Book Studio broadside well within a tradition of promoting this first novel in the Aubrey/Maturin corpus.

Was it serendipity that 54 years after an advertising maven promoted a new release, we hit upon the same strategy for our edition? Perhaps. Maybe it was just a good idea then and still is today. Or, as perhaps there was something deeper at work… a phenomenon that might not appear out of place in Mr. Wynd’s Wunderkabinett. Whatever the case, I am grateful to Mr. Wynd for generously allowing me to share this original promotional material for Master and Commander.

Coming Up Next…

In my next missive, I will return to the design of our edition of Master and Commander, exploring the revolutionary changes in type that took place during the late 18th century and how those changes influenced the design of our book. Until then, fair winds and calm seas.

Hey Stuart - if you look at the centre of the coat of arms in the images above, you will see a very small shield. This was the arms of the European royal House of Hanover. Here it is enlarged from Wikipedia:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/House_of_Hanover#/media/File:Royal_Hanover_Inescutcheon.svg

In 1714, British Queen Anne of the house of Stuart died leaving no children of her own. Under the terms of the "Act of Settlement of 1701" the British Crown passed to George Louis (Georg Ludwig) who was at that time ruler of Hanover, a province of the Holy Roman Empire.

So when Georg Ludwig became King George the First of Great Britain, he was also at the same time ruler of Hanover. As such the coat of arms of Hanover were added to the coat of arms of Great Britain.

In 1837 when King William the Fourth died and Queen Victoria came to the throne, under the law of Hanover a woman could not rule Hanover so the new ruler of Hanover was the Queen's uncle Ernest. As such the shield with the arms of the House of Hanover was in 1837 removed from the coat of arms of the United Kingdom as Queen Victoria was no longer ruler of both the UK and Hanover.

I apologize, but I cannot see the differences in the coat of arms in the above? Would you be able to show detail pictures and perhaps highlight the differences?