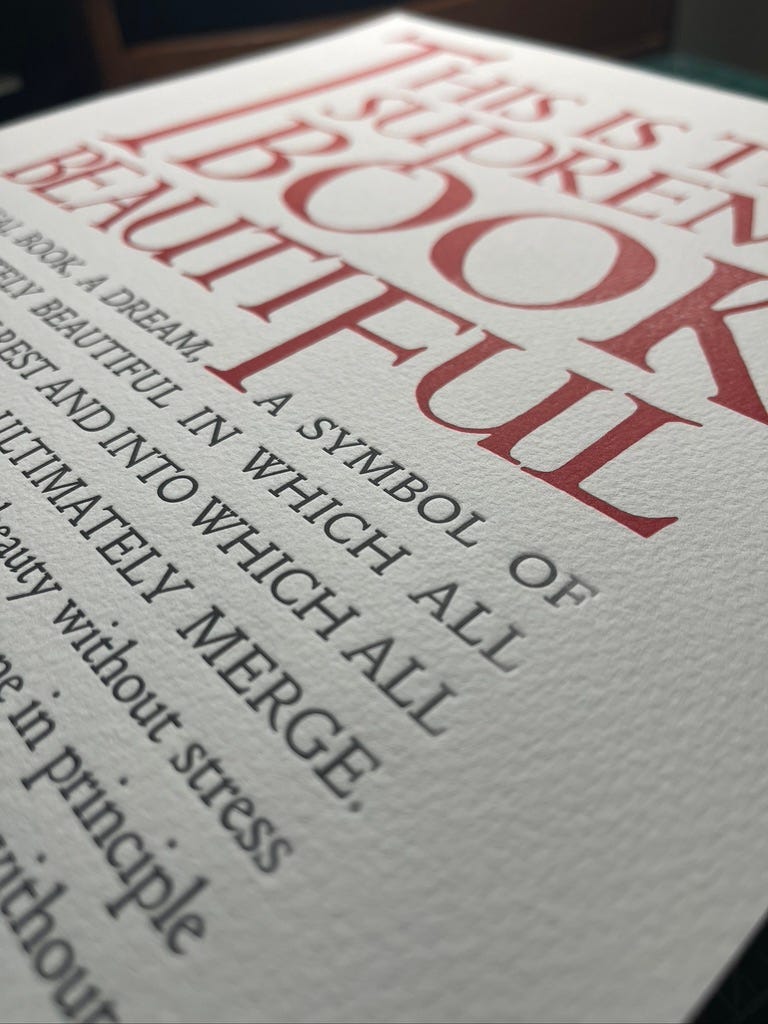

Thomas James Cobden-Sanderson's essay, The Ideal Book or Book Beautiful: A Tract on Calligraphy, Printing and Illustration & On the Book Beautiful as a Whole (1900) helped define the Arts and Crafts Movement and has served as the philosophical foundation for the Fine Press movement of the last 100 years. Today, it continues to inspire and drive Ampersand Book Studio. It is no surprise, then, that it serves as the inspiration for two Ampersand Book Studio projects: 1) our line-by-line letterpress facsimile of the original essay, and 2) our "The Book Beautiful" limited edition art print.

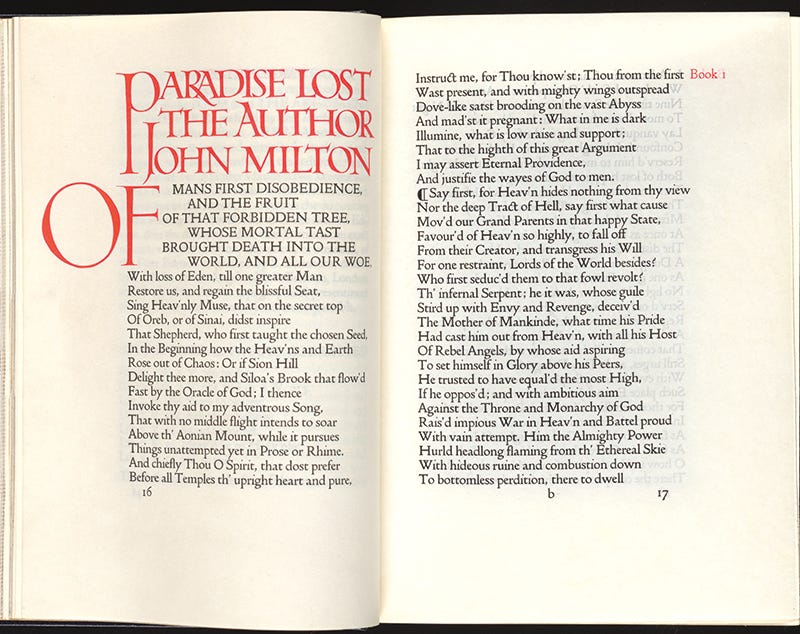

Cobden-Sanderson (1840-1922) was one of the luminaries of the Arts and Crafts artistic movement in England in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1884, he left his law practice to establish the Doves Bindery followed by The Doves Press in 1900. The Doves Press is renowned for printing some of the finest English-language books of the 20th century, including a five-volume Bible and an edition of John Milton’s “Paradise Lost.”

The Arts and Crafts Movement

The Arts and Crafts movement – a term coined by Cobden-Sanderson in 1887 – was a response to the mass production, division of labor, and de-skilling of workers brought about by the Industrial Revolution. Social critic and writer John Ruskin had argued against this “servile labour,” instead advocating for labor dignified by handwork and craftsmanship. Many of the proponents and practitioners of the Arts and Crafts Movement – including William Morris and Cobden-Sanderson – were socialists and opposed the alienation brought about by industrialized production. Although these social critics engaged in efforts at social reform, many eventually sought to to recreate meaningful labor through artistic craftsmanship.

Aesthetically, the Arts and Crafts Movement valued the process of crafting more than a specific set of aesthetic values. As Monica Obniski has written for the Metropolitan Museum of Art,

"The Arts and Crafts movement did not promote a particular style, but it did advocate reform as part of its philosophy and instigated a critique of industrial labor; as modern machines replaced workers, Arts and Crafts proponents called for an end to the division of labor and advanced the designer as craftsman."

That said, some traits – such as simplicity, connections to nature, and focus on the textures, colors, and grain of materials (be they stone, wood or paper) – did emerge as frequent, but not universal aesthetic choices by Arts and Crafts creators. The artistic movement was exemplified by the textile designs and books published by William Morris (England); the architecture and furniture of Charles Rennie Mackintosh (Scotland), Greene and Green (United States), the early work of Frank Lloyd Wright (United States), and Gustav Stickley (United States); the American art pottery of Roycroft, Rookwood, Newcomb, and many others; and the stained glass of Louis Comfort Tiffany (United States).

Personally, I have always been drawn to the aesthetics of perfect simplicity and artisan craftsmanship. One of the most memorable places I have ever visited – 15 years ago now – is the Gamble House in Pasadena, CA. The great architectural masterpiece by brothers Charles and Henry Green, the home was designed and built in 1908-09 for David and Mary Gamble (of the Proctor & Gamble fortune), and is seen by many as the pinnacle of Arts and Crafts architecture in the U.S. Organic lines, handcraft, incorporation of nature, and celebration of materials – especially wood – make it a remarkable architectural statement.

Photos of Gamble House from https://gamblehouse.org/

It may be of no coincidence that I was honored to spend twenty years of my life working with a Native American nonprofit organization – Tohono O'odham Community Action – whose programs included efforts to nurture basketweaving traditions within the tribe.

Baskets by members of the Tohono O'odham Basketweavers Organization (top to bottom): Sadie Marks, Virginia Lopez, and Esther James

Although from a very different cultural context, Tohono O'odham baskets share a focus on perfect simplicity, artisanal skill, connection to nature, and handwork that was so valued as a part of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Indeed, as Monica Obniski observes, a "Native American undercurrent developed during the Arts and Crafts movement, as evidenced by fashionable Indian-style baskets and textiles featured in Arts and Crafts exhibitions and publications. Many collected baskets to display in their Indian corners, which may have inspired Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933) to design a hanging shade in an Indian basket motif:

The Ideal Book or Book Beautiful: Art & Crafts Fine Presses

In The Ideal Book or Book Beautiful: A Tract on Calligraphy, Printing and Illustration & On the Book Beautiful as a Whole, Cobden-Sanderson applies core aesthetic tenets of the Arts and Crafts movement to the book. In it, he lays out a design aesthetic of perfect simplicity in which typography and illustration do not "substitute for the beauty or interest of the thing thought and intended to be conveyed by the symbol, a beauty or interest of its own, but,on the one hand, to win access for that communication by the clearness & beauty of the vehicle, and on the other hand, to take advantage of every pause or stage in that communication to interpose some characteristic & restful beauty in its own art." He continues:

The Book Beautiful, then, should be conceived of as a whole, & the self-assertion of any Art beyond the limits imposed by the conditions of its creation should be looked upon as an Act of Treason. The proper duty of each Art within such limits is to co-operate with all the other arts, similarly employed, in the production of something which is distinctly Not-Itself.

He concludes with the passage presented in the Ampersand Book Studio art print.

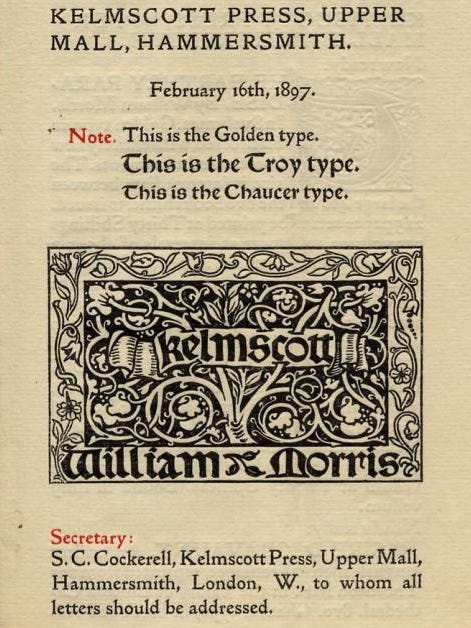

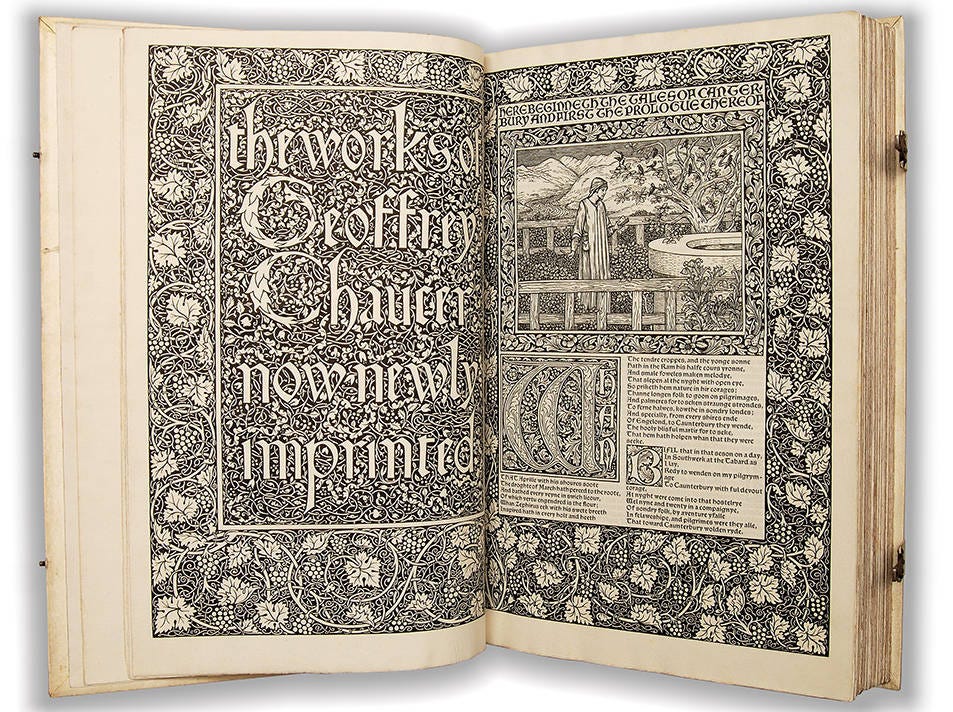

Cobden-Sanderson's essay – and the entire ethos of his Doves Press – was not only a response to what he saw as the soullessness of industrial book production, but also a critique of one of his fellow Arts and Crafts Movement leaders, William Morris. From 1891-1898, Morris' Kelmscott Press published over fifty books in very limited quantities. Following the values of handwork and craftsmanship he shared with Cobden-Sanderson, Morris drew on the design cues of 15th century books. As part of this neo-Gothic approach, he commissioned new typefaces and artwork for his editions.

Top image: wikicommons. Bottom two images: University of London

Clearly, Morris' publications met the goals of raising up craft, artistry, and handwork. However, it is easy to see a degree of aesthetic excess in his work. The content of the book – the words themselves – become almost an after-thought in some Kelmscott Press editions.

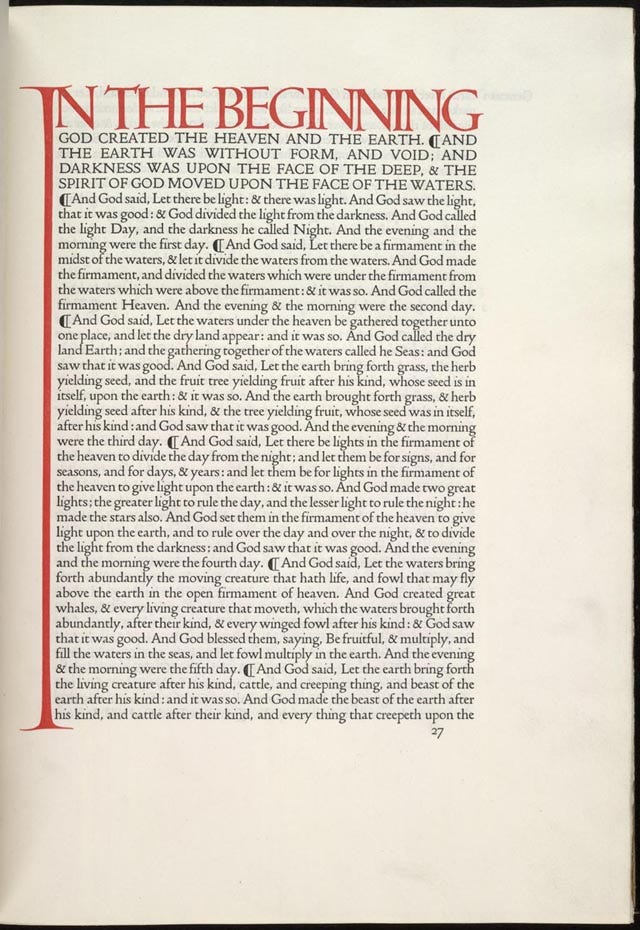

It was this perceived excess to which Cobden-Sanderson seems to argue in his essay – and in the publications he offered through his Doves Press. Cobden-Sanderson too developed a new typeface, one much more classical than that of his friend, Morris. Moreover, he reserved decorative flourishes for "the especial beauty of the first or introductory page and of the title, and for the especial beauty of the headings of chapters, capital or initial letters, & so on" (in the case of typography) and "the illustrative content itself should be formal… so as literally to illustrate, and not to dim by over brilliancy the rest of the subject matter" (in the case of illustration).

Cobden-Sanderson's essay serves, in many ways, as a mission statement for the publications of his Doves Press. The implications of his argument in The Ideal Book can be seen in pages of all Doves Press editions.

Cobden-Sanderson seems to focus more the experience of reading a book than did Morris. For him, the words – the content and artistry of the author – remained the focus. All other design elements – paper, typography, illustration, binding, decoration – are to operate "in subordination to the whole," each highlighting and augmenting the content. Simplicity and the small gesture appears in every Doves Press book. Simply binding. Clear and classical typefaces. Limited illustration. Beautiful materials, textures, and simplicity replace complexity and ornament.

Pages from the Ampersand Book Studio edition Cobden-Sanderson's essay, a line-by-line recreation of the original Doves Press version.

The Doves Press was a major influence on the “fine press” movement of 20th century in both Great Britain and the United States. For the past century, fine presses have worked to create "the book beautiful," works of printing and binding art that continue the tradition of the Kelmscott Press and the Doves Press. Historically, presses such as the Roycroft Press, Harbor Press, and Hammer Creek Press created tremendous works in the 20th century. Today, the fine press movement continues in the remarkable work of presses such as Arion Press in San Francisco, Thornwillow Press (Newburgh, New York), and the Petrarch Press (Oregon House, California).

Today, Ampersand Book Studio continues to be inspired by the aesthetic vision of T.J. Cobden-Sanderson and the Arts and Crafts Movement. All of our editions strive to create books and artwork that centers, highlights, and raises and celebrates the written word.

For those interested in reading Cobden-Sanderson's entire essay, a letterpress facsimile copy by Ampersand Book Studio is currently developing an edition that will offer 100 copies in paper, 12 copies in the original vellum, five in leather, and ten in pages. Lots of updates on the creation process will be here on Substack over the coming weeks. So, subscribe to be notified of this content.

In the meantime, our letterpress art print with a quote from Cobden-Sanderson's essay is currently available in our shop. Thanks for for being a part of our journey!