With the end of our Kickstarter campaign two weeks ago, we have moved into high gear on the creation of the edition of Master and Commander. Although we are still about a month from starting the printing process – we await delivery of the paper which is on a ship somewhere between France and the U.S. – there is still much to do. Printing and posting the HMS Polychrest Broadside and the 1803 map of Mahón Harbor has kept us busy in the workshop, while we have been burning the midnight oil by completing the final copyediting. This has left little time for finishing the long-promised article on the revolution in 18th century typography; rest assured, it is almost complete. In the meantime, I wanted to share a few thoughts on the unglamorous topic of copy editing.

On Copy Editing

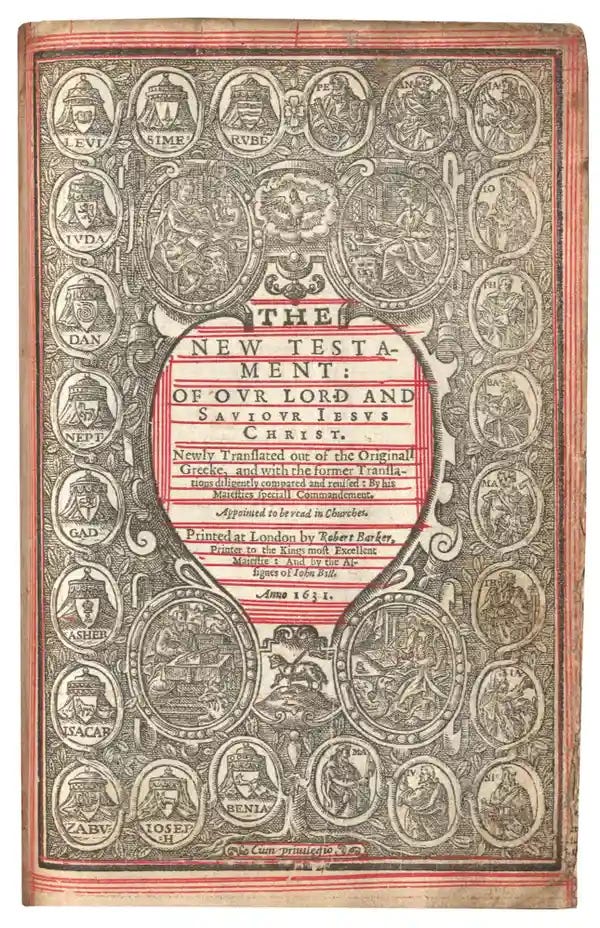

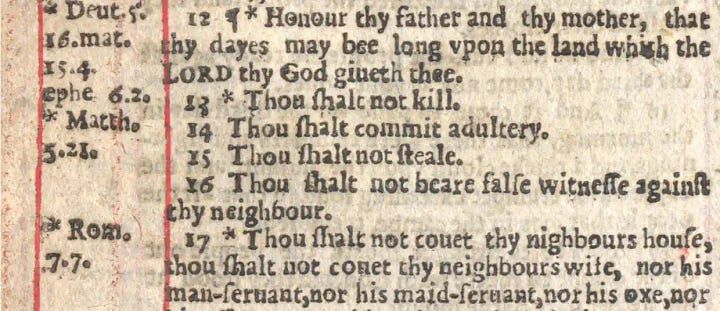

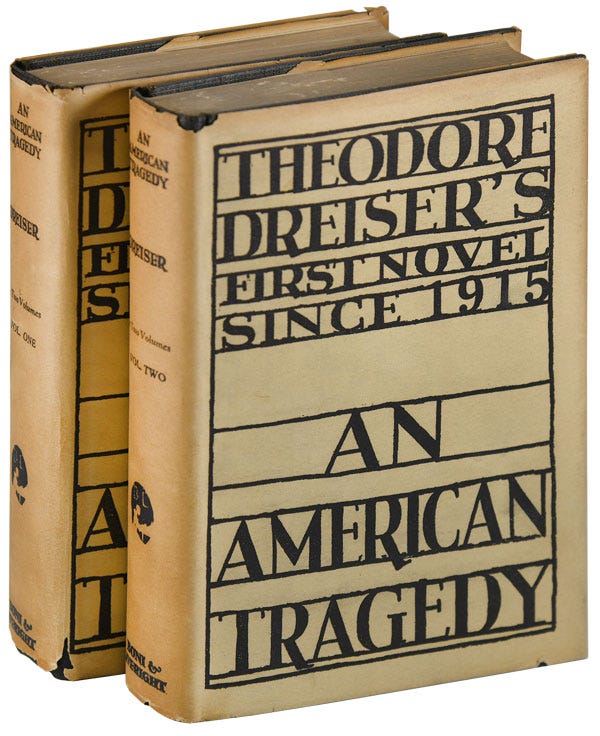

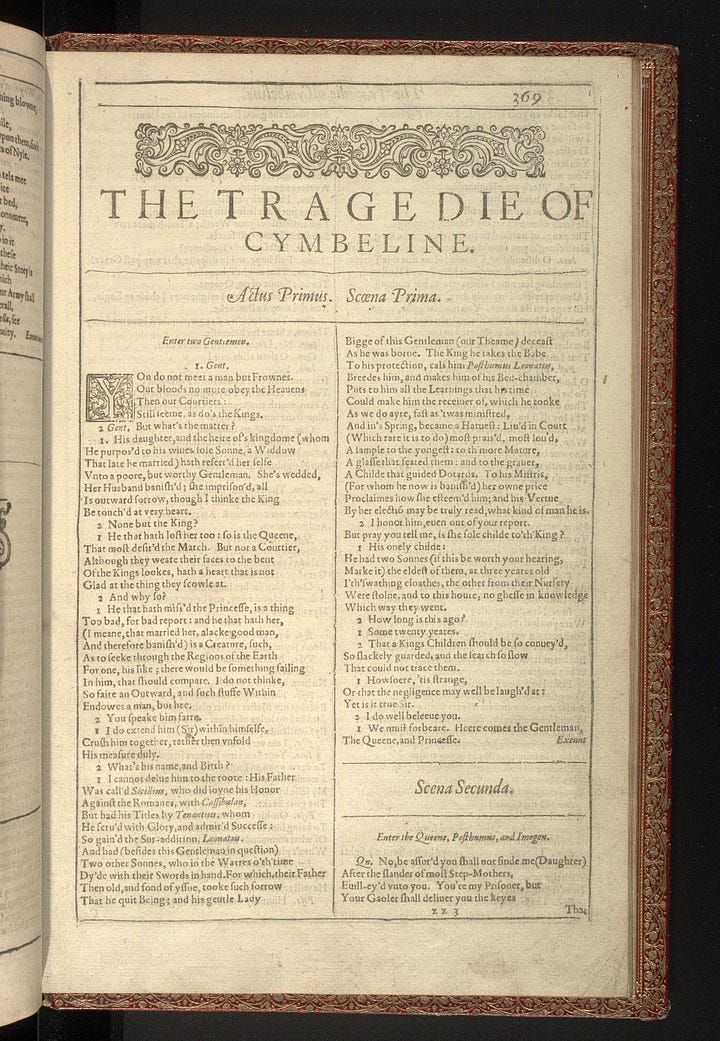

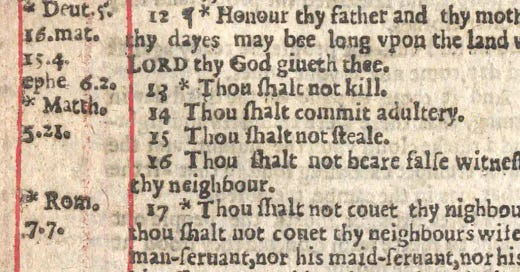

Words, and punctuation, matter. A lot. It is worth getting right, as no level of typography, design or craft can overcome a poor text. We have all had the experience of being fully immersed in a story only to be jarred out of our reverie by a typo. Some typos have become infamous, such as that of the so-called “Wicked Bible” (1631) in which the seventh Commandment reads “thou shalt commit adultery.” (I admit to wondering if this was, truly, a typo or if it was the intentional work of a mischievous typesetter.) In the first edition of Theodore Dreiser’s 1925 novel, An American Tragedy, a passage reminiscent of our own book read “...harmoniously abandoning themselves to the rhythm of the music—like two small chips being tossed about on a rough but friendly sea.” Even Shakespeare’s Cymbeline was changed forever when the doubled N (referred to as a homogeneous digraph) of his character Innogen were mistaken for a single M in the first published editions. Ever since, Imogen has been known as one of the “most tender and most artless” of the Bard’s characters.

With this in mind, I have been working with a friend (and early Ampersand Book Studio patron), Mr. Tyler Sample, to make sure that this edition of Master and Commander is as Mr. O’Brian imagined it. That means more than just simply spell-checking the text. In a work of more than 140,000 words, there are almost always errors of spelling or italicization or punctuation, and previous editions of M&C have not been immune. After all, knowing when to italicize “Victory” requires human decision-making; does it refer to the ship (italicized) or is it a proclamation of success? When does “Formidable” refer to Admiral Keith and when to an 80-gun French ship? The efforts and work of Mr. Sample have helped guarantee that the text of our volume will be in great shape. A glass of wine with you, sir!

Two technical elements – punctuation and italicization – have proved most challenging in preparing our text. Until going through the proofreading process, I never realized how complex – and unconventional – much of Patrick O’Brian’s use of punctuation is. Take for example,

‘Any damned tarpaulin can manage a ship in a storm,’ he went on in a slighting voice, ‘and any housewife in breeches can keep the decks clean and the falls just so; but it needs a headpiece’ – tapping his own – ‘and true bottom and steadiness, as well as conduct, to be the captain of a man-o’-war: and these are qualities not to be found in every Johnny-come-lately – nor in every Jack-lie-by-the-wall, neither,’ he added, more or less to himself.

In that one sentence, we have six quotation marks, seven commas, one colon, one semicolon, three dashes, eight hyphens, and a full stop. Is it any wonder that copy editing takes time? This does not even address the need to get passages such as this one correct:

Let the angle YCB, to which the yard is braced up, be called the trim of the sails, and expressed by the symbol b. This is the complement of the angle DCI. Now Cl:ID = rad.:tan. DCI = I:tan. DCI = I: cotan. b. Therefore we have finally |: cotan. b = A1:B1:tan.2x, and A1 cotan. b B tangent2, and tan. 1x = A/B cot. This equation evidently ascertains the mutual relation between the trim of the sails and the leeway...

In the above, I am still not sure about “tangent2.” At least two previous editions of Master and Commander have the “t” as superscript. And I wonder if the “2” is meant to be superscript, thereby meaning “squared.” I am leaning toward “tangent2”). Unless, of course, one of our crew is a mathematical sort who can steer me in the right direction.

Even italicization can be more challenging than using a simple “search/replace” command. Take, for example, the name of Jack’s command, HMS Sophie. Following convention, the name of ships is italicized. However, when referring to the crew of a ship – the Sophies – italics are not used. Of course, the possessive – as in “the Sophie’s crew” – requires both normal and italic type. And when the name appears in a long italicized passage (such as Jack’s official dispatches), everything is reversed. With more than 70 ships mentioned in the text – some scores or even hundreds of times – getting this right takes time.

Will our text be perfect? It seems unlikely. However, we have undertaken every effort to make sure that Mr. O’Brian’s words – and not embarrassing typos – amuse the reader. So, as of Friday, we have the final proofs now complete, ready to begin the process of making the printing plates.

Sending Maps and Broadsides

We are about halfway finished preparing the HMS Polychrest recruiting broadside and the 1803 map of Mahón Harbor for shipping. They should all be in the post on Tuesday. For backers based in the U.S., this means that they should begin to arrive late next week. For those of you in the rest of the world, please be patient. Some of our post – even when sent first class/air mail – has been taking quite a while; one recent package to Australia took more than a month. But rest assured, these rewards will begin their journey to you next week.

Not sure it's the tan^2 as you stated. cot = 1/tan. Therefore, I would expect some cot^2 unless the equation was re-expressed in sin or cos.