Embracing the “E” Word

So much damage has been done in the name of the “E” word… efficiency. Indeed, the processes of seeking economies of scale and mass production led to many of the social and aesthetic problems critiqued by key thinkers of the Arts and Crafts Movement like T.J. Cobden-Sanderson and his intellectual mentor, John Ruskin. Yet efficiency within limits is not necessarily a problem. After all, printing with moveable type sought to make it possible to spread the written word more efficiently than through copying by hand. It made possible the reproduction of pages – and the ideas contained in them – at a scale never before imagined.

Prior to the 1440s, the vast majority of European books were hand-written. Scribes –mostly monks and, as recent scholarship indicates, nuns – would laboriously copy and illuminate books. Much of this was done on parchment – a specially prepared animal skin – as paper would not see widespread use until the 14th century.

Diagram of the four seasons and four cardinal directions, from a copy of Isidore's De Natura Rerum: copied by 8 female scribes at Munsterblisen, c. 1130–1174, Harley MS 3099, f. 156r]

When Johannes Gutenberg invented his press in 1440, it was not only the introduction of moveable type that made it so revolutionary. It was also his creation of mechanisms that 1) produced rapid, equal pressure on the platen (the plate which presses the paper against the type), and 2) a moving table on which paper or parchment sheets could quickly and easily be changed. He also popularized the use of oil-based inks to replace the water-based ones that been used in hand-written books for centuries.

Peter Small demonstrating the use of the Gutenberg press at the International Printing Museum. (Wiki Commons)

Gutenberg's "letter press" process – in which ink is rolled onto a plate of metal type and paper is pressed onto the plate by a platen – remained at the heart of every printing press from the 1440s through the 1880s. While the presses themselves became more complex – with the introduction of everything from steam power to automatic paper feeders – the basic process of a platen pressing a piece of paper onto a plate to which ink had been applied remained the same.

Koenig's 1814 steam-powered printing press. (Wiki Commons)

Despite the introduction of "offset" printing in 1870s – now the most common form of commercial printing – letterpress printing remained common well into the second half of the 20th century. Today, with offset and digital printing technologies, letterpress printing is often reserved for special projects – such as artwork and wedding invitations – where the tactile nature of the printing, such as deeply impressed or debossed letters, is desired.

Cobden-Sanderson & the Division of Labor at the Doves Press

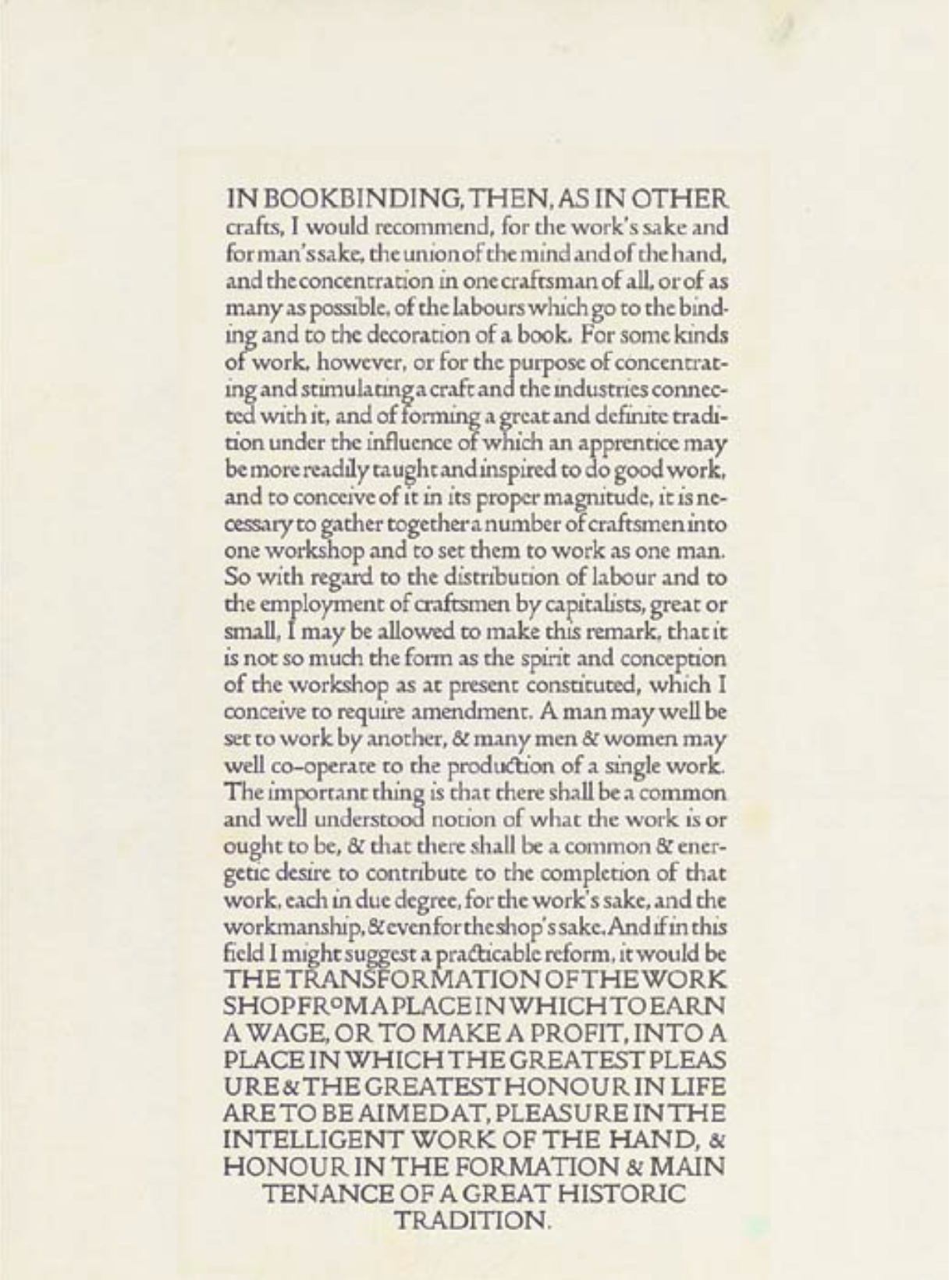

Even as he sought to return to artisanal production at the Doves Press, T.J. Cobden-Sanderson understood that the process of creating multiples of beautiful books required things like the division of labor, specialization, and at least enough efficiency to allow for books in editions with hundreds of copies. Indeed, the very first items ever printed with his newly created typeface, he expressed his view of how a book workshop should ideally operate.

The first item printed by the newly established Doves Press in 1900 (https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-4601821).

In this 1900 broadside – which was limited to just 25 copies for the employees and friends of the press – he tacitly acknowledges that division of labor is necessary for the efficiency of book production.

Indeed, in establishing the Doves Press as a commercial venture, there was always a tension between Cobden-Sanderson’s focus on craft and a more “practical” approach advocated by his partner in the business, Emery Walker. Throughout its sixteen-year existence, tensions at the Press – between the efficiency of a mercantile concern and artistic vision – contributed to the eventual rupturing of the relationship between the partners, and ultimately, to the closing of the press and destruction of the Doves typeface. However, at the earliest stages – when The Ideal Book was originally published – there were many skilled craftspeople involved in the actual production… from compositor J.H. Mason and pressman Henry Gage-Cole to the mostly unnamed artisans who sewed and bound the books by hand. Indeed, there is very little evidence that Cobden-Sanderson actually did much – if any – of the production himself. While he was the visionary of the Doves Press, the actual production was largely left to others. Thus, the need for skilled craftspeople operating complex technologies (e.g., engraving of metal matrices to produce type and printing presses) was a part of the original production process at the Doves Press

Printing Our New Edition

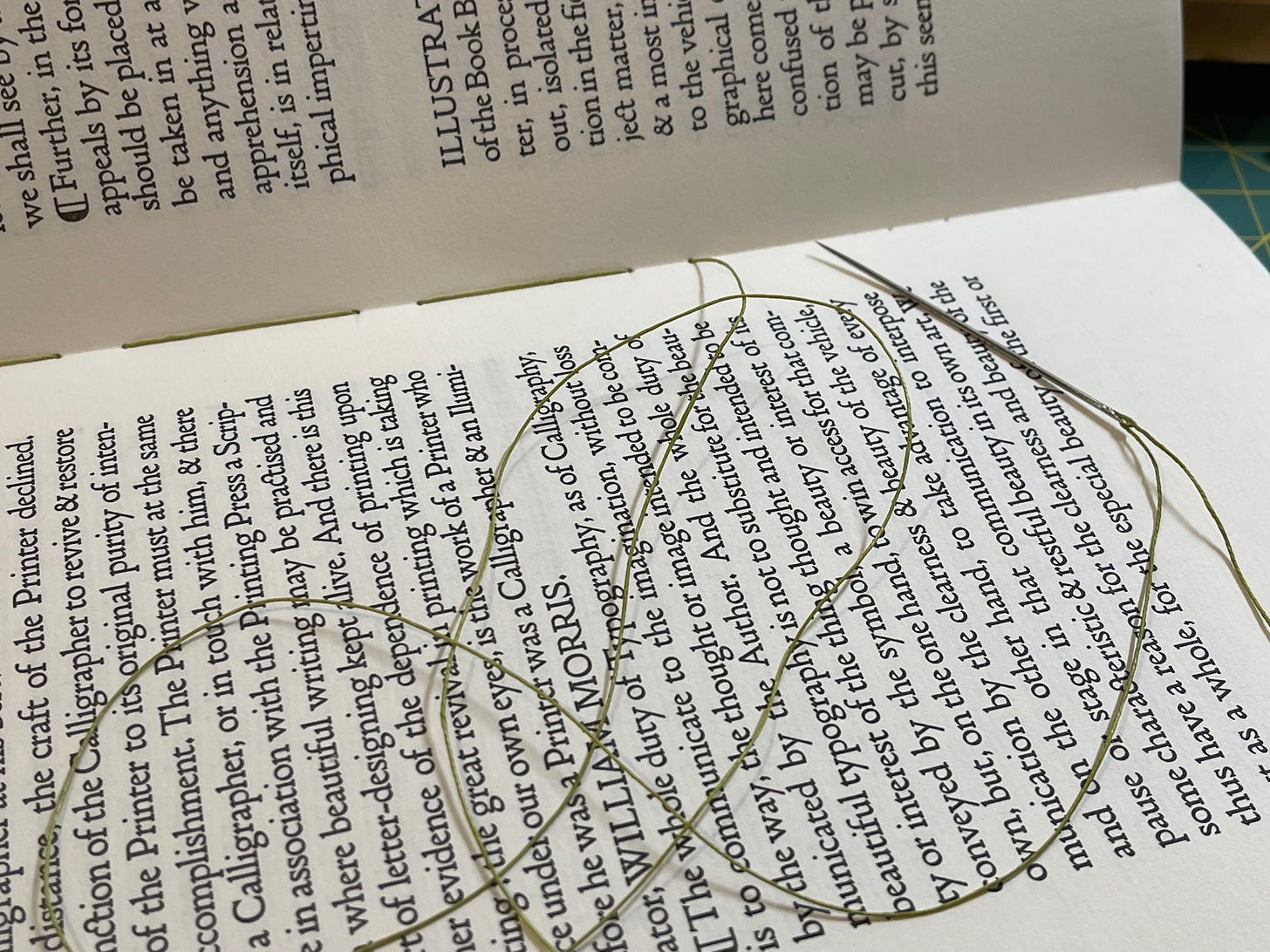

Unlike the division of labor at the Doves Press – albeit a humane one in which there was a “common and well understood notion of what the work is” – each step in the creation of the Ampersand Book Studio edition of The Ideal Book is done by a single individual. Every process – from the electronic typesetting to printing, from the sewing of the signatures to binding in vellum – is being undertaken by my own hands.

This holistic approach to production is both a joy, and potentially, a problem. I often worry that in this approach I am in danger of being a “jack of all trades and master of none.” As Cobden-Sanderson seems to have known, specialization can often lead to a degree of expertise. I have already alluded to the challenge set before me trying to live up to the skills of people like pressman Henry Gage-Cole.

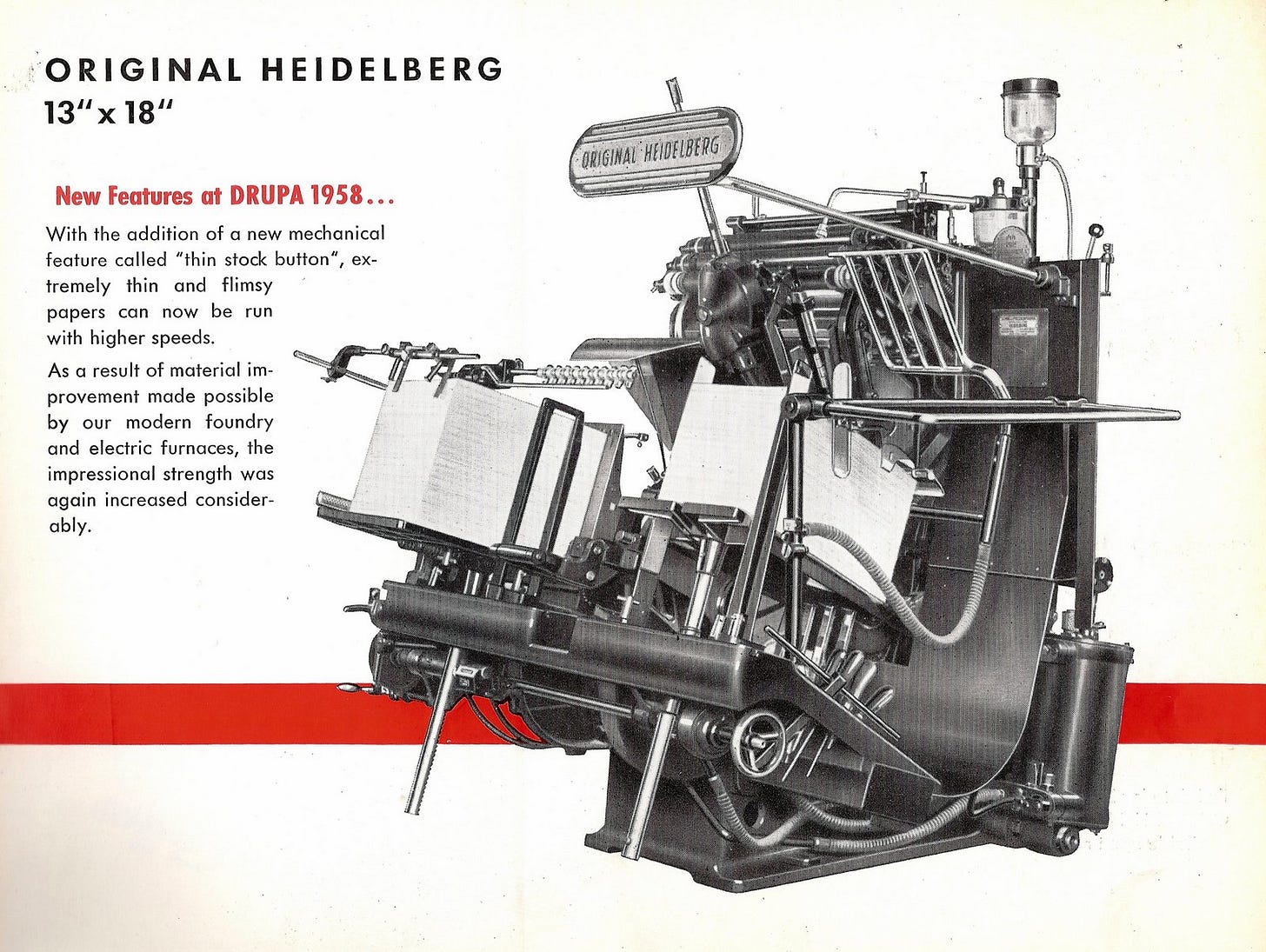

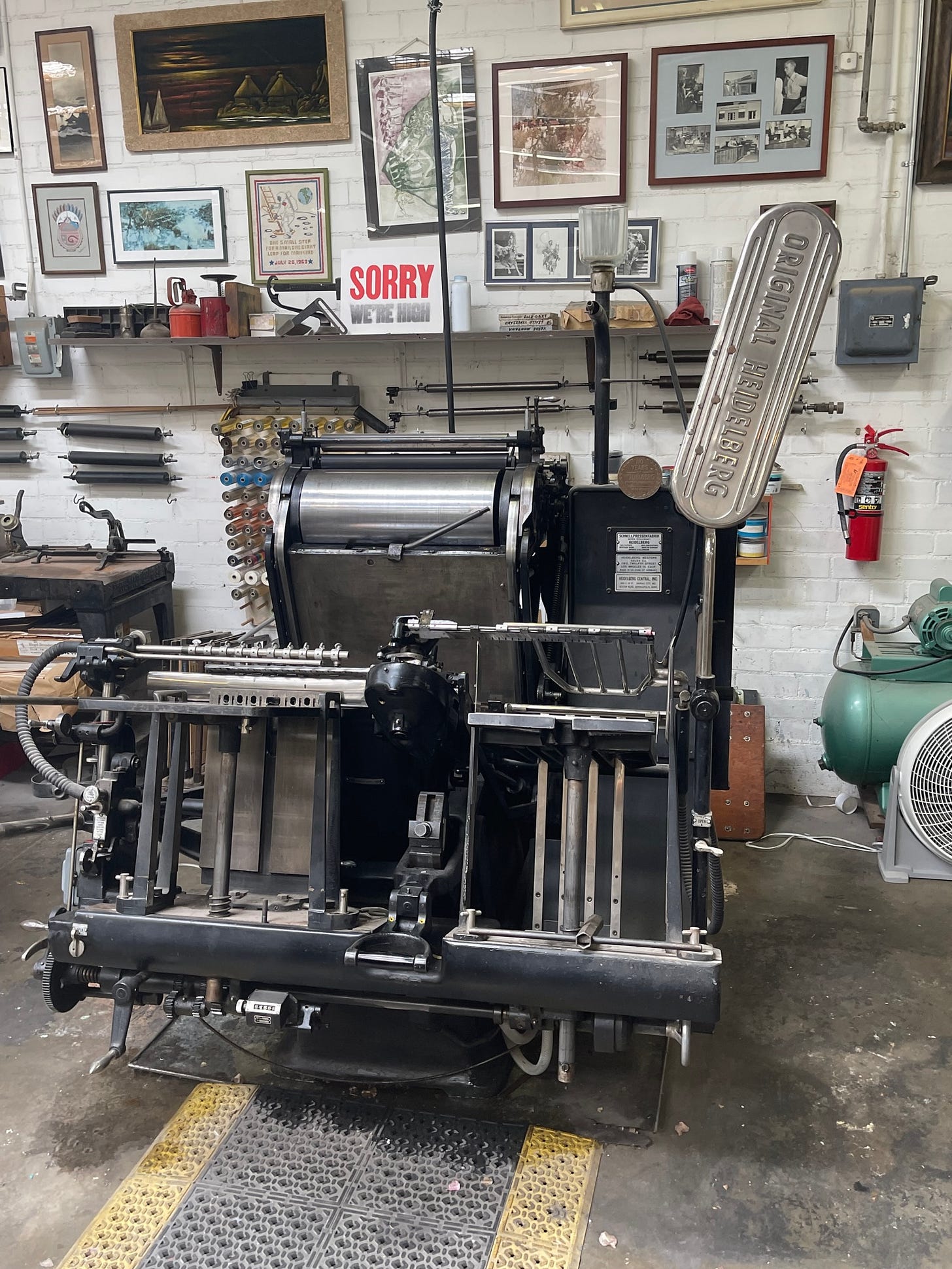

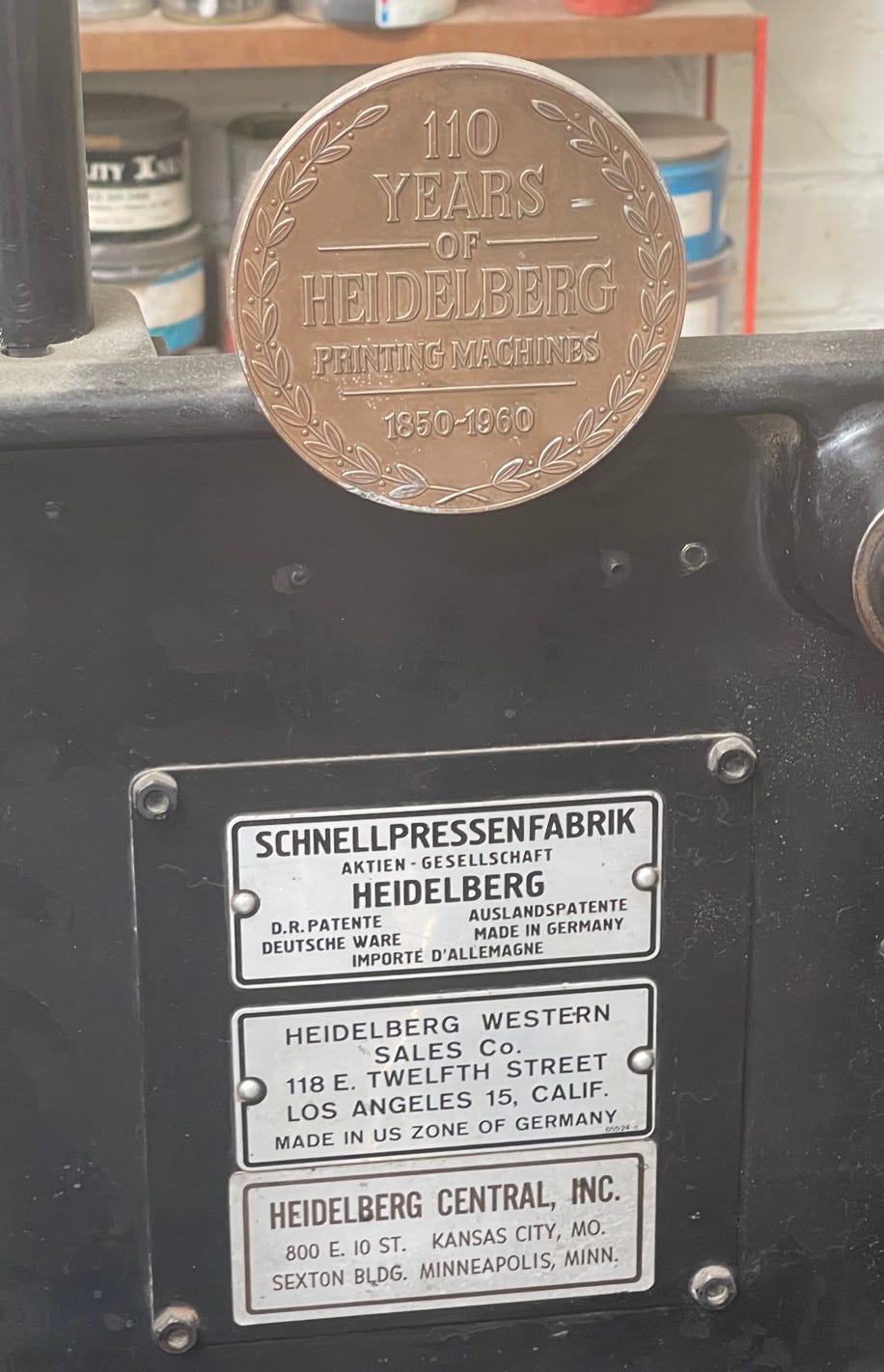

What is one way of addressing this? Well, in my case, it is the use of one of the greatest pieces of letterpress printing technology since Gutenberg: the Heidelberg Original “Windmill” press. Introduced in 1923 by the Heidelberger Druckmaschinen company in Germany, this marvel of mechanical engineering was produced with only minor changes through 1985. It is widely considered to be the apex of platen press design, perhaps with only Heideberg’s cylinder presses introduced decades later surpassing them.

Our edition of The Idea Book has been printed on a 13”x18” Original Heidelberg.

Our particular example, at Betts Printing in Tucson, Arizona, was made in 1949 when Germany was still an occupied zone. It has produced hundreds of thousands – perhaps millions – of impressions. It would be fascinating to see a history of everything that one of these presses printed over the course of their long lives.

Combining flywheels and pistons, rollers and valves, vacuums and fans, gears and levers, and “windmill” arms that grab and release paper, the Heidelberg may seem a far cry from the press of Gutenberg. Yet, at its heart, it still uses the basic innovations of Gutenberg's first press: a flat platen presses a single piece of paper against inked raised type. The rest just makes distributing ink and feeding paper faster and more automated than a press of 500 years ago. But even mass production is not new; by the Renaissance in Europe, presses could churn out more than 3000 pages per day.

Eric Doyle of Betts Printing demonstrates the operation of the Heidelberg Original press on which I printed The Ideal Book. All of that hissing and whirling of the Heidelberg Windmill is merely in service of keeping ink on the plate and individual sheets of paper fed onto the platen. [If video is not loading, it can be viewed here.

However, the greatest strength of the Heidelberg Windmill is not efficiency. Rather, consistent quality is the real benefit it offers. People generally agree that the broad shift to offset (and eventually digital) printing was not made because of quality. The way in which letterpress printing employs plates and pressure to place ink on the page leads to a superior reading experience. Lines are crisp and clear. Contrast is excellent. There is a tactile feel to the impression (even when the ink just “kisses” the page). And the Windmill was made to make such inky impressions perfectly, time after time. Or at least once it is set up properly. Every aspect of the printing process is adjustable on the Heidelberg….

The rate of ink flow from the “fountain” (i.e., reservoir) to the rollers is controlled by manually turning more than a dozen valves and adjusting the lever that controls rotation speed of the distribution roller.

Height adjustments on three of the rollers increases/decreases the amount ink deposited onto the plate for each impression.

The pressure of the impression is finely adjustable to make the plate just barely kiss the paper with the ink, make a deep debossed impression, or anywhere in between.

The platen requires a process of “make-ready” in which tympan paper, tissue paper, acetate, and even clear packing tape are used to adjust the “packing” on the platen, thereby ensuring a consistent impression across the entire page.

Gauges to ensure fine registration are engaged, disengaged and/or adjusted.

The speed of operation, power of suction that picks up each sheet of paper, rate at which the stack of paper feeds, and much more is adjustable.

Each of these adjustments is made for the sake of achieving a high-quality and consistent impression of ink on the page each and every time, be it for a limited edition of ten art prints or the 1,282 pages in a reproduction of the original Gutenberg Bible.

The learning curve for all of this adjustability, however, is where skill and experience matters. For each problem that appears on the printed page, there are two, three, even more possible causes with an equal number of adjustment solutions. If, for example, the type at the bottom of the page is lighter than at the top, it could be a problem with the contact the ink rollers are making with the bottom of the plate. Or it could be that the plate is slightly low there, requiring “make ready” to add a thin piece of tissue paper to the packing on the platen. Although I can usually identify the source of the problem on the first try, there are still times when I – and, I have been assured, most press operators – go through a process of trying one “solution” only to have to reverse it and try another one. This can be time consuming and frustrating. However, once everything is set, the Heidelberg Windmill will provide tremendously high-quality prints consistently.

Like in a human relationship, the stages of my relationship with the Heidelberg Windmill are complex. It was love at first sight – its hissing and clacking, its beautiful industrial design, knowing it could make me happy by creating lovely books. But then the nervousness and questioning sets in. What if it does not reciprocate? What if it wants to move faster than I do? It looks high maintenance. It demands attention and asks for accountability. It has its own way of doing things, asking me to compromise. It might be worth it, I decide, to learn and appreciate its idiosyncrasies. But that process can be frustrating, even intimidating. Ultimately, however, once we learn how each other works, how to appreciate the quirks, how to work with each other’s expectations, the relationship deepens and strengthens. Eventually, I hope that I come to fully understand it at a deep level, appreciating it for who – err…. what – it is.

Learning by doing, which often means learning from your mistakes, takes time. In the case of printing books – even small editions of short volumes such as our edition of The Ideal Book – a degree of efficiency is essential. The next book Ampersand Book Studio plans to create, for example, will require more than 70,000 press impressions for just 177 copies. Should each and every one of these impressions require a sheet of paper to be placed by hand, one-at-a-time, on the platen of a manually-fed press, it is hard to imagine the amount of labor and time that would be needed to produce such a volume. Yet, even with all of these advantages, our next project will take an estimated three months – eight hours a day, five days a week – to print. Claims of “efficiency” are relative when compared to commercial offset and/or digital printing.

Tristan printing sample pages for The Ideal Book in August 2022.

William Faulkner once wrote, “You don’t love because: you love despite; not for the virtues, but despite the faults.” While I do understand this – and know that after 36 yers with my wife, she definitely has loved me “despite” – I do not think this is an either/or situation. It is possible to love someone (or something) because of their idiosyncrasies, quirks and imperfections. Indeed, I think that this may be the secret to good long-term relationships: to love because and despite, understanding that the virtues and faults are of a piece. By that standard, my love of the Heidelberg Windmill press has matured. It is a complex relationship, one in which the wants and needs of the machine are part of the attraction.

Update on Production & Coming Up

All of this is to say… the printing of The Ideal Book has been completed. Now on to binding!

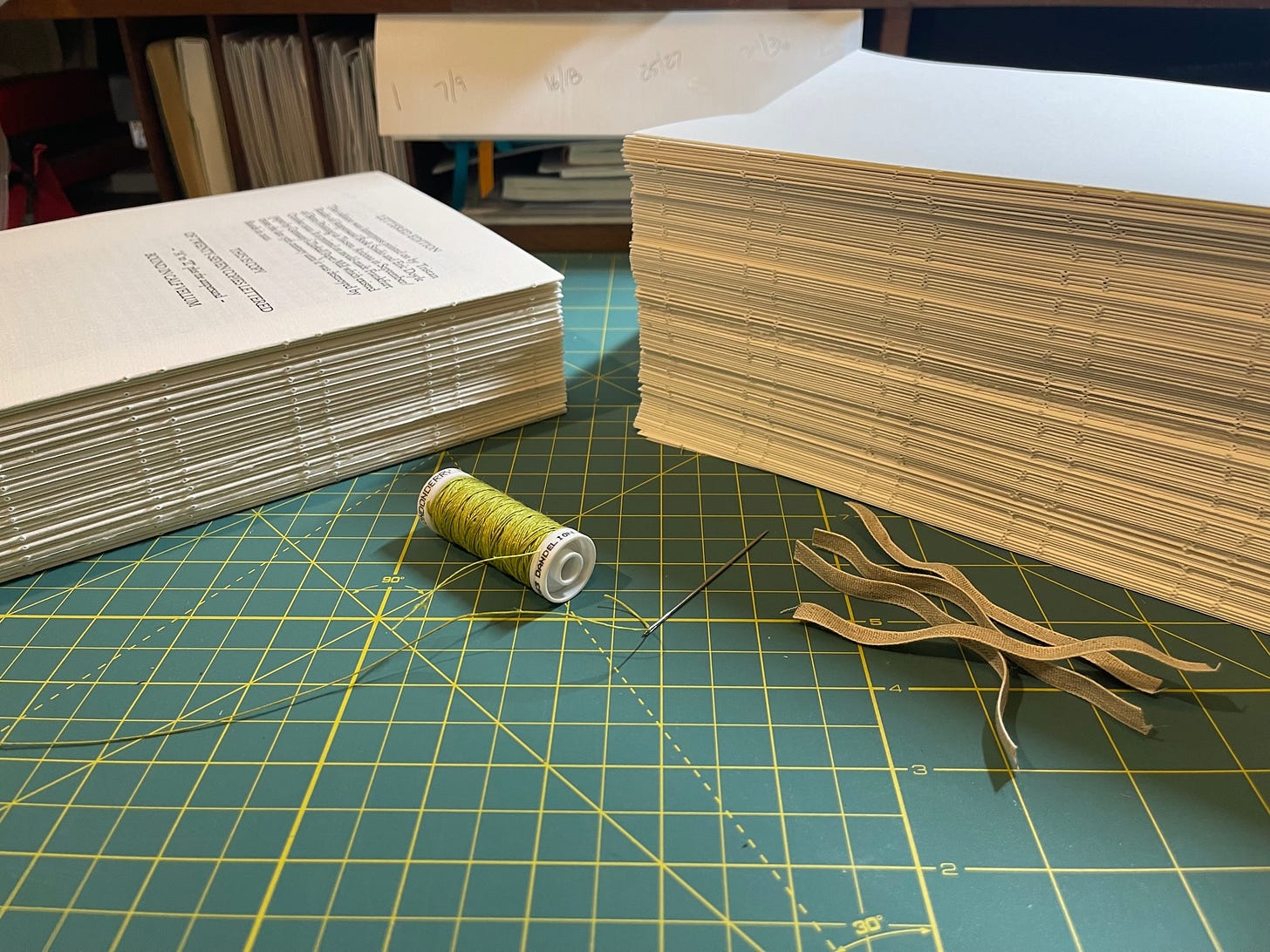

I have started sewing and binding copies of our edition of The Ideal Book. I am on track to ship all pre-ordered copies by the end of November, quite possibly earlier.

Top: Signatures of The Ideal Book ready to be sewn into a book block. Bottom: The distinctive green sewing thread used by the Doves Press is used here as well.

In our next Substack post, I will explore some of the unique binding and design elements used by the Doves Press and how I am reproducing them in the 21st century.

Ordering The Ideal Book

A limited number of copies our edition of The Ideal Book are still available for pre-order on our website. Shipping for all pre-orders is anticipated to be in plenty of time for holiday gift giving.