As we make progress with the binding of Master and Commander, I have found myself thinking a lot about the tools used in bookbinding. As almost any craftsperson can attest, a good tool is a pleasure to use, making the job both easier and better. This is certainly true during our current stage of production – sewing, rounding, trimming, and backing of the book block. Perhaps the most time consuming of all of the steps in our bookbinding process, each of these steps requires purpose-built tools. Take a look at a few of them in action.

I want to take some time to introduce some of the tools that make our work possible – as well as a few of the very talented people making such specialty tools today.

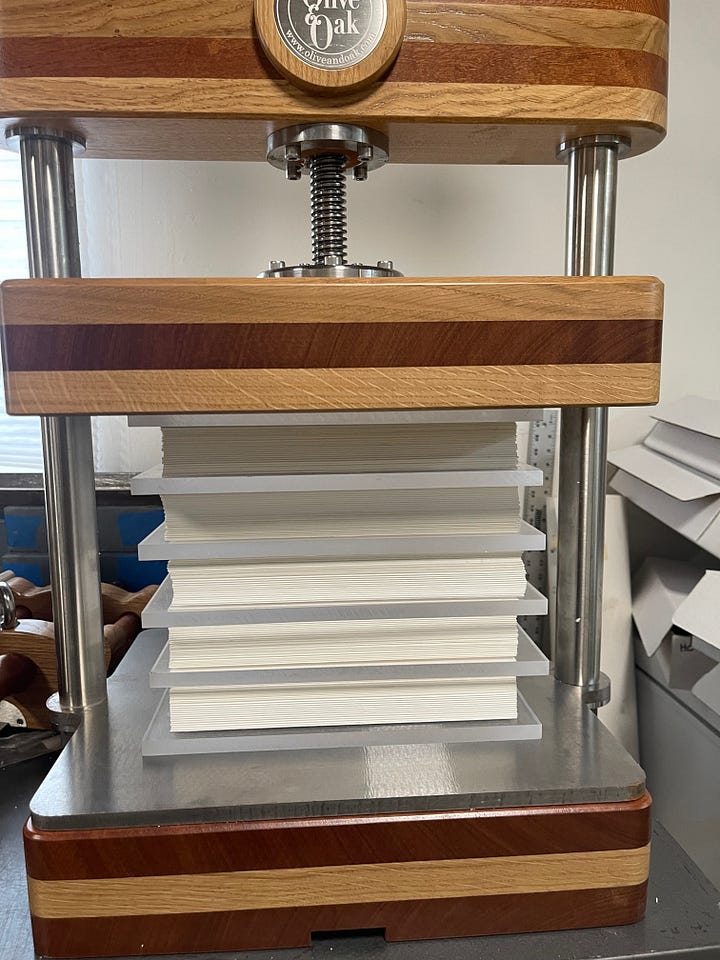

Olive and Oak

In his workshop in northern Portugal, English woodworker James Oliver makes the world’s finest bookbinding presses. As proprietor of Olive and Oak, James combines craftsmanship, precision, art, beauty and love. He has taken the craft of toolmaking to a new height. His full-sized Harlequin Press, for example, is a thing beautiful, showing his talent as a furniture maker.

As a fellow craftsperson (and former very amateur woodworker myself), I was curious to know more about James’ work and how he come to specialize in making tools for bookbinders.

At the time that I first made anything bookbinding related I was doing about 50/50 mobile carpentry service and fitted furniture type projects for people's homes out of a shared workshop. I was lucky enough to be in one of the very few remaining factory buildings anywhere near the centre of London that hadn't been converted into luxury flats or offices (the owner was a proper old-school socialist chap, already in his 70s at the time, who loved the community of artists, textile workers, metal and wood workers, musicians, glass workers, etc that occupied his building. He'd refused all offers to sell to developers - including a couple that involved briefcases full of cash being waved under his nose - and was content to shuffle around the place four or five days a week changing light bulbs, unblocking toilets or just passing the time of day chatting to tenants. So the location and way-below-market rent meant I was doing ok; I made a decent living doing something I was competent at and mostly enjoyed.

There were times, however, when I had an itch that I felt needed scratching: essentially I was always working on someone else's project at the level of finish, detail, material quality, etc decided by the client. Don't get me wrong, I was grateful for all the work I was getting - which afforded me a comfortable life - it's just that, unsurprisingly, most clients' desires were budget-led and so my creative drive didn't get that many chances to really show itself. In short, there was at times a small sense of unfulfillment, which occasionally trespassed upon the borders of frustration.

At that time I was married to a bookbinder (Nicky Oliver, Black Fox Bindery) whom I accompanied many times to design binding exhibitions, the occasional award ceremony and the like, and the after-event pub visit. Put a bunch of bookbinders in a pub and the topic of conversation rarely ventures beyond bookbinding and its accoutrements. So although I was kind of an outsider with regards to most of the talk, I could see the potential of a crossover at some point with most bindery equipment being mostly made of wood.

So a few years of osmosis of all that chat along with some helpful suggestions led up to the day I first set eyes on a laying press. It was old - probably late 19th or very early 20th century - and made of wood and cast iron. I was instantly captivated by this curious apparatus and began to bombard its owner (Mark Cockram, Studio 5) with questions. Mark is always busy, but took the time to answer most of them. What I took away from the exchange was, a) the old, solid equipment was preferred by many binders, b) it was not being made to that level any more, so the remaining pieces held their value, c) the cheaper end of the market for binding equipment was already fairly well populated; all of which condensed into d) the light bulb moment of here was something I could do on my own terms and for which, hopefully, there could be a market for. I say light bulb moment but that makes it sound like I thought of everything myself, whereas it was a combination of all I've said above, suggestions and support from those I mentioned above (and more), some luck and a leap of faith when I took some drawings and all the money I had to an engineer in order to make the metal elements for a pair of prototypes. A year or so later I took both prototypes to the Society of Bookbinders' biennial conference and sold them both that weekend. The rest, as they say, is history.

In terms of his design process, James employs a strategy that is familiar to many people who do book design and binding:

How can I make this thing as robust, functional and beautiful as possible? Once I know exactly what is expected from the user of whatever it is, I set out to make it pretty, make it to last and make it work - the way many things were made before the world got taken over by bean counters. More recently I've tried to fashion a style, so that someone might know it was one of my pieces before seeing the nameplate. More recently still I've been thinking about doing some more 'out there' pieces; still within the parameters of robust and functional, but pushing the beautiful more towards art. It could be a disaster, we'll see.

I knew that I would love to use one of James’ larger presses, but one would take up too much space in my small studio. Thankfully, James has addressed this common concern, creating his Pygmy Press. Featuring the same level of detail and beauty as his larger presses, this is, perhaps, the one press to rule them all, helping the bookbinder accomplish so many tasks… gluing up, trimming edges with the included plough, backing the spines, decorating or gilding the edges of the book, and more.

Two of these beautiful tools grace our workspace at Ampersand Book Studio. Used almost every day, their beauty inspires my work. However, as beautiful as they are, it is their precise functioning that makes them stand above the (albeit very small) field of competitors making presses today. As all wonderful tools do, my Olive and Oak presses combine three often contradictory traits: faster, easier and better. Compared to lesser presses, for example, achieving proper alignment of the book for backing is consistent and precise. This makes achieving the mushroom-shaped spine of a backed book much more consistent while also making it faster to accomplish. No longer do I have to spend ten minutes fiddling to get the book precisely aligned to create 3mm shoulders along the front and back spine of the book.

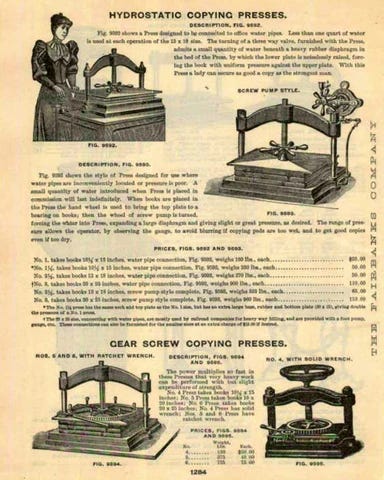

So, when I started thinking about a larger nipping or standing press for the studio, it made sense to check in with James. You see, in order to assemble the pages of the book, we collate and gather sets of the printed sheets and fold them into the signatures. In the case of Master and Commander, four sheets are gathered and folded in half, creating a finished signature of 16 pages. Repeated 23 times, these signatures are then collated to create the pages of the book. However, even having creased the folds of each signature using a bone folder, they still want to open and fill with air. In order to coax the pages into the flat shape we need for proper binding, the entire book block must be placed into a press under pressure and left for 12 to 24 hours to relax and consolidate into an even book block.

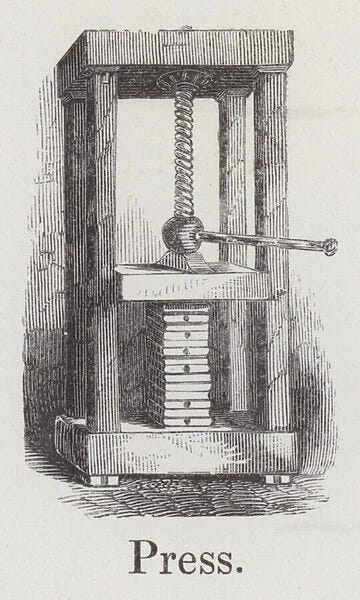

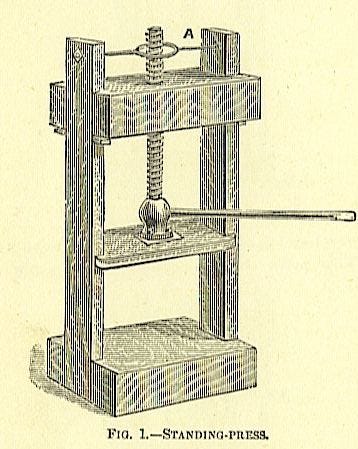

These days, many artisan bookbinders use heavy, antique copying presses made from cast iron for this process. Although not initially made for bookbinding – they were more often used for making copies of letters prior to the widespread use of carbon paper – these small, heavy presses have become a mainstay for small-scale bookbinding, including that of Ampersand Book Studio.

Often ornately decorated, these presses were a common sight in offices of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Like so many cases of “make do” tools, however, these copy presses have significant limitations for the creation of editions rather than one-off books. With very limited space between the top an bottom plates (usually 3-4 inches/8-10 cm), they can only press a single volume at a time. With each copy of our book needing to spend a day under pressure, using a single copying press can be a bottle neck to production. For our 127 copies of Master and Commander, it could take months just to press the book blocks!

The solution for many small binderies today is to simply use multiple copying presses – referred to as nipping presses when used for bookbinding. In my studio, however, I often find myself facing a problem that urban planners often confront: real estate is limited and outward expansion is not an option. So, like binderies of the past (and urban planners in cities worldwide), I began to think vertically, seeking a standing press such as those used in binderies for centuries. However, unlike the ubiquitous copying press that was in almost every office for over a century, standing presses are a very rare commodity, indeed.

So, once again, I turned to James Oliver. For a few years, James had been pondering the creation of a large nipping/small standing press. While he had not had the time to move beyond designing it on paper and limited prototyping, I really wanted, nay, needed, such a press. And I knew that James was the person to create one. So, although James had not made such a press before, I was confident enough to commission one sight unseen. He recently shared:

I thought about making nipping presses for years before the almost three years I spent making the prototype that you have now. All of the earlier ideas had too much metal in them because I couldn't figure out, or didn't have enough confidence in, other ways of using wood. I wanted to include wooden elements in it or else I'd only be assembling an engineer's work and there'd be little of mine in it and where's the fun in that? Also my earlier woodworking machinery wasn't the big industrial stuff that I've traded up to over the years and I was much more limited earlier on. Buying a big old percussion nipping press to make the laminations for the base and platen was the best idea I had this year.

[The commission] was an enormous confidence booster for me and also perhaps the gentle kick up the butt that I needed to bring the project that had been bouncing around my head - with a few elements completed - from being under the bench to taking shape upon it. It was quite a learning curve and a rewarding experience, especially since seeing it working.”

You can imagine my excitement when a large wooden crate was delivered outside of my studio here in Tucson last month. What, exactly, would I find inside?

I was delighted to discover exactly what one would expect from such a wonderful craftsperson: a powerful, functional standing press with the added benefit of great beauty. Within just a few minutes of unpacking it, five copies of Master and Commander – nearly 2000 pages folded into 125 signatures – were under pressure in the press. Form and function were united in James’ press, a tool created by a true craftsman that will help my own craft – both functionally and as an aesthetic inspiration – for many years to come. And it will, most assuredly, do the same for future generations of binders who may adopt it after I have left this mortal coil, so robust is its build.

Many thanks to James for taking on this commission, and for creating tools of great utility and beauty. In James’ work, I find another craftsperson who seems to share many of the same values as my own: simplicity and beauty in service to function; hand craftsmanship; creating human value through meaningful labor; and unity of form and function. As I have written previously, these values – articulated most clearly by proponents of the Arts and Crafts Movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries – sit at the heart of the fine press movement of today.

Dimitris Koutsipetsidis

When hand binding of books was the norm, specialist toolmakers were much more common than today. However, with mechanization and industrialization of book creation, demand for specialty tools declined to the point that many tools essential to the craft were no longer being manufactured at all. Obtaining proper bookbinding tools became harder and harder. Supply of antique tools is limited, and many of them have reached the end of their life cycle, no longer able to perform the function for which they were designed.

In response, a new group of toolmakers has emerged over the past couple of decades: artisan bookbinders themselves. Facing a lack of proper tools and frustrated by trying to adapt existing tools to their needs, some of the world’s top bookbinders and restorers set out to make the tools they needed for their own work… and they have shared these with others. One such person is Dimitris Koutsipetsidis, a remarkable artisan from Athens, Greece.

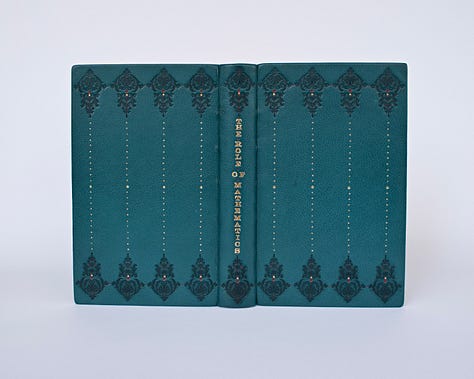

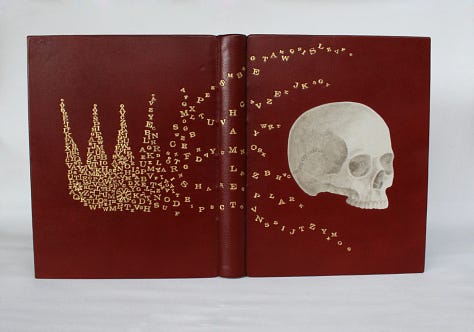

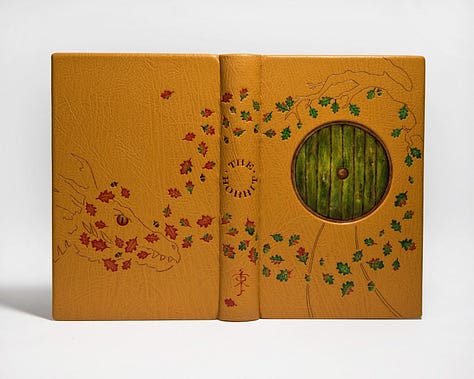

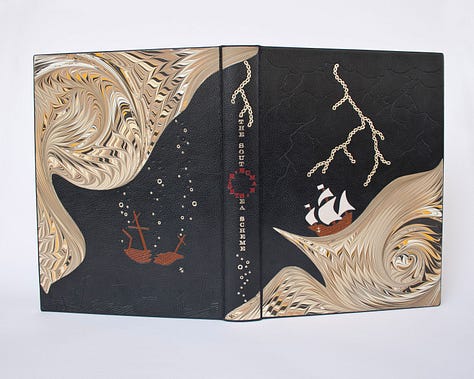

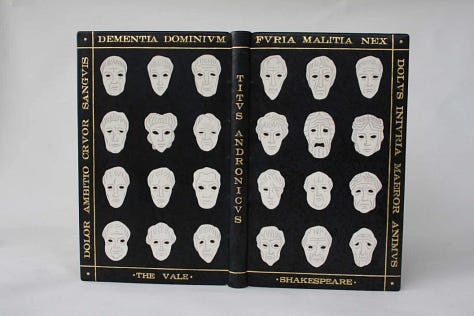

Dimitris’ work ranges from classically designed, hand-crafted book to stunningly creative modern design bindings.

Unable to find many of the tools he needed in order to execute his artistic vision, Dimitris began to create tools himself, eventually sharing them with others. As he says:

Τools are the extension of the artisan’s hand, the means by which skill is transformed into something tangible. There’s something infinitely fascinating about unlocking the ability to create your own, even more so sharing them with other fellow artisans. It feels like discovering a whole new world underneath the one you are passionate about; entwined with it but completely different, where different rules apply. I make my tools, first and foremost, for the most demanding and unforgiving client there is, myself, knowing I will use them on my own work. As such I want them to feel, look and perform great.… Over the years my toolmaking has evolved alongside my bookbinding skills, one propelling the other forward, and enabling me to introduce new tool sets and revisit my existing ones, improving and expanding them.

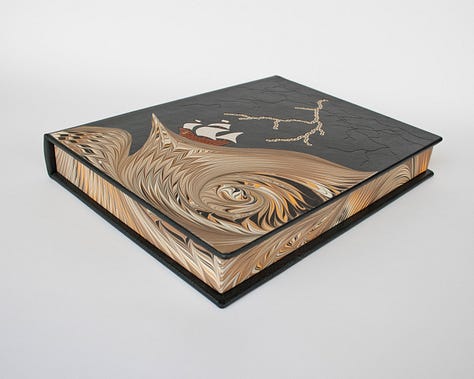

One essential design element of our edition of Master and Commander is the five raised cords on the spine the book. These bands create visual interest and tactile pleasure while revealing the structural nature of the linen cords onto which the book is sewn. Such raised bands are so attractive that some people actually add false versions onto the spines of book, glueing nonfunctional material to the spine before covering it with leather. As those who have read some of my previous posts might surmise, such faux raised bands to run counter my design aesthetic, one in which which form should always follow, highlight, and celebrate function. However, whether real or faux, one of the challenges posed by raised bands is the need to make sure that the leather stretches over and fully adhere to the underlying cords, creating crisply defined raised bands.

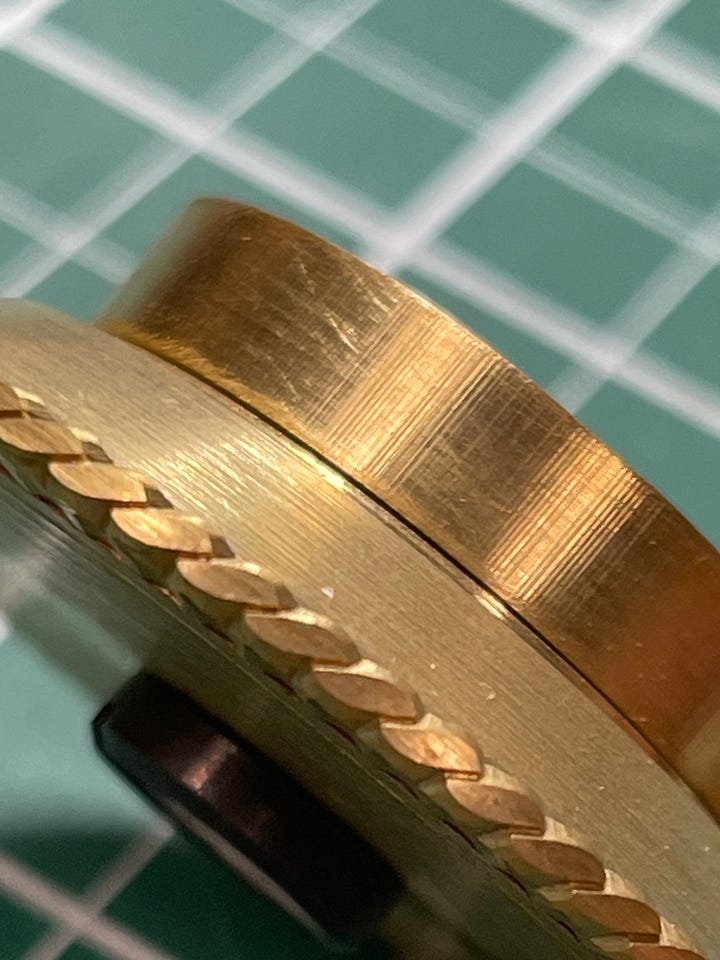

Many binderies turned to the use of band nippers. Made out of metal, these tools look like a pliers and a hammerhead shark had a baby. Their wide, flat jaws can be easily adjusted for different width bands. However, they require continual adjustment and a firm grip, and the steel ones available commercially can easily mar or ever cut the delicate, thin leathers used for bookbinding. Dissatisfied with those available, Dimitris developed his own version of band nippers, crafted out of softer brass at precise angles that are, in the words of the brilliant bookbinder, Karen Hanmer, “crisp but not sharp, smooth but not slippery.”

However, Dimitris was not 100% satisfied. One day he heard from a fellow bookbinder who had muscle strain after decades of work. “She had trouble using band nippers due to the hand pressure required. Band sticks immediately came to mind.” Band sticks are hardly a new idea. A simple piece of hardwood into which a groove has been made, the band stick is rocked back and forth over the leather, stretching and pulling it over the underlying cord. Although simple and effective, the benefits of the band stick may be offset by the fact that wood has oils that, when rubbed over leather, over and over, can leave stains. Moreover, band sticks are relatively short-lived, prone to developing splinters and chips, imperfections which will mar the book’s fine leather. So, knowing the limitations of wood, Dimitris set out to create an extremely simple, yet completely new, tool: the brass band stick.

Dimitris calls his brass band sticks “an updated version of the old-timey tool, one that is more robust, precise, friendly to leather and comfortable to use,” and he is absolutely right! They are the kind of tool I love: simple, yet perfectly designed to do its job perfectly. When making individual books, perhaps the constant adjustment and pressure of the band nippers is not too burdensome. But when creating 127 copies of a book, having a simple, perfectly sized tool save lots of wear and tear on my increasingly old joints.

I love these tools for their simple perfection. They were designed by someone with a deep understanding of their use, who created them for his own practice. The depth of knowledge shows in every detail.

Other Artisan Toolmakers

James and Dimitris are just two of a small cadre of toolmakers whose thoughtful, well-crafted, artisan tools grace our studio. Here is a sampling of a few others whose tools are critical to our work and used in our studio regularly.

Jeff Peachey

Jeff Peachey is a New York City-based book conservator who has worked on everything from a Gutenberg Bible and other incunabula (books printed prior to 1500) to important 20th century bindings such as those by T.J. Cobden-Sanderson’s Doves Press. Jeff also researches, designs, and sells some wonderful bookbinding tools, all of which have been developed for his own practice.

Perhaps what most opened my eyes to how a simple, yet specialized, tool can transform the process of crafting was my discovery of the frottoir and the grattoir. In English bookbinding traditions, the rounding of the book is accomplished primarily by using a small hammer to address glancing blows to the spine of the book. Although it gets the job done, I find it to be a risky endeavor; one misplaced blow and the spine can get smashed. Then I learned of these tools more commonly used in continental Europe. As Jeff Peachey writes of his first use of an antique frottoir, “I was surprised how easy it was to gently control the backing process and tweak the cords into alignment. I had much more control compared to using a hammer.”

Jeff offers his own design which he calls a Kaschtoir that combines elements of the frottoir, the grattoir, and the German kaschiereisen. Like with Dimitris Koutsipetsidis’ brass band sticks, Jeff made many small but very important refinements that add up to something much bigger. He engaged in a long process of research, testing of antique tools, and prototyping in creating his version. It was this precise design, the result of many hours of labor and literal decades of experience, that led to Jeff’s design.

I can honestly say that this tool design has changed my bookbinding life! It makes backing both much easier and of a much higher quality than using a backing hammer. This tool offers greater control, more precision, and much more consistent results. I now achieve that perfect ‘mushroom’ shape to the spine. It is especially useful when the book has raised cords, as you have to hammer between the cords which can be difficult. While I still use a backing hammer to help finish backing, the bulk of the work is done by my frottoir.

Unfortunately, I have to mention the question of intellectual property here. Before I knew of the origin of the tool in Jeff’s workshop, I purchased a version through an Etsy shop. Although well-made and useful, it appears to be a direct copy of Jeff’s design, albeit in brass rather than stainless steel. The market for such specialized tools is not large and the amount of knowledge, research, experience, creativity, time, and prototyping that goes into refining new tools should not be underestimated or devalued. So, I encourage anyone seeking out fine bookbinding tools to seek out artisans such as James Oliver, Dimitris Koutsipetsidis, and Jeff Peachey, creators who add deep value to the small, vibrant world of bookbinding. I happily use other tools made by Jeff’s own hands here in my studio, and I continue to look forward to any future designs he creates, knowing they will make my work even better.

Bookbindesign

Not far from England’s southern coast, Kevin Noakes – the craftsman behind Bookbindesigns – engraves remarkable brass tool and type for use in decorating books. “From a young age, I was very craft orientated and enjoyed making something from nothing,” writes Kevin. “I continued with my creative passion and began work as an engraver making bookbinding tools for 30 years.”

For our edition of Master and Commander, Kevin has produced a couple of line pallets and rolls with a simple rope design.

Moving Ahead

Making beautiful books without tools and toolmakers – while possible – would be much less satisfying in terms of both the process and the results. Every time I turn the wheel on an Olive and Oak press or feel the heft of a metal frottoir, I delight in the creative process.

In the coming several weeks, we will finish the slow process of sewing, rounding, backing and trimming our edition of Master and Commander. Then it will be on to some of the more decorative elements of the binding: end bands and edge decoration. More on those as we start that work.

Our Next Project

Even as my hands work on our edition of Master and Commander, my mind has started thinking about our next project. As I hope you saw in our Kickstarter campaign for Master and Commander, countless hours, hard work, and even dreams go into the planning of each of our editions. While my hands are busily working in the studio, my heart and mind begin to conceive of what it next. While one book is in production, the conception and design of the next is also in the works. So, within the next couple of weeks, we will be announcing our next book – a creative collaboration I can hardly wait to share. Fear not, however. It will not launch on Kickstarter until next year and production will not begin until Master and Commander is finished. First things first. But by announcing the project early, my collaborators and I will be able to share our entire design process, welcoming you to follow the journey from the very start.

I so enjoyed this love letter to excellent craftspeople and their work.