I took a few days off of binding Master and Commander this past week to embark on a new printing adventure. You see, a couple of months ago, my friend and master printer Bill Whitley made me an offer I couldn’t refuse. Bill had heard through the grapevine that I had started looking for a good cylinder press to support the continued growth of Ampersand Book Studio. He thought he had a solution. However, one such press was not what Bill had in mind. “I have three Miehle V50s,” he wrote. “I will sell you one for $500, two for $250, or all three for free.” I understood. The demands of space are always there for those who 1) do this work out of small studios, and 2) who have a tendency to accumulate orphaned, old printing and binding equipment. But what Bill wanted to pass on was precisely what I needed.

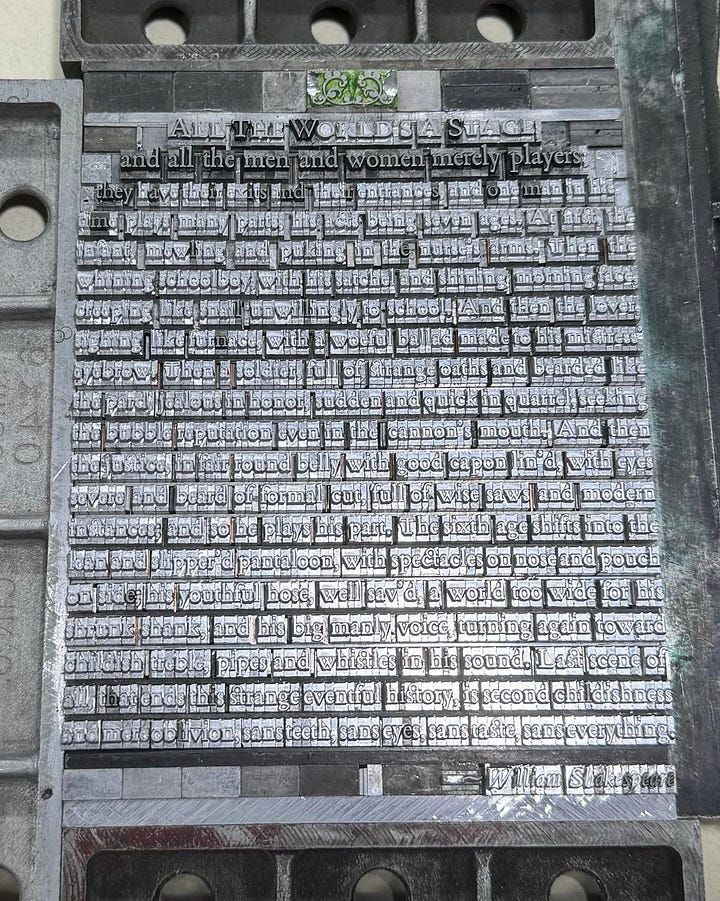

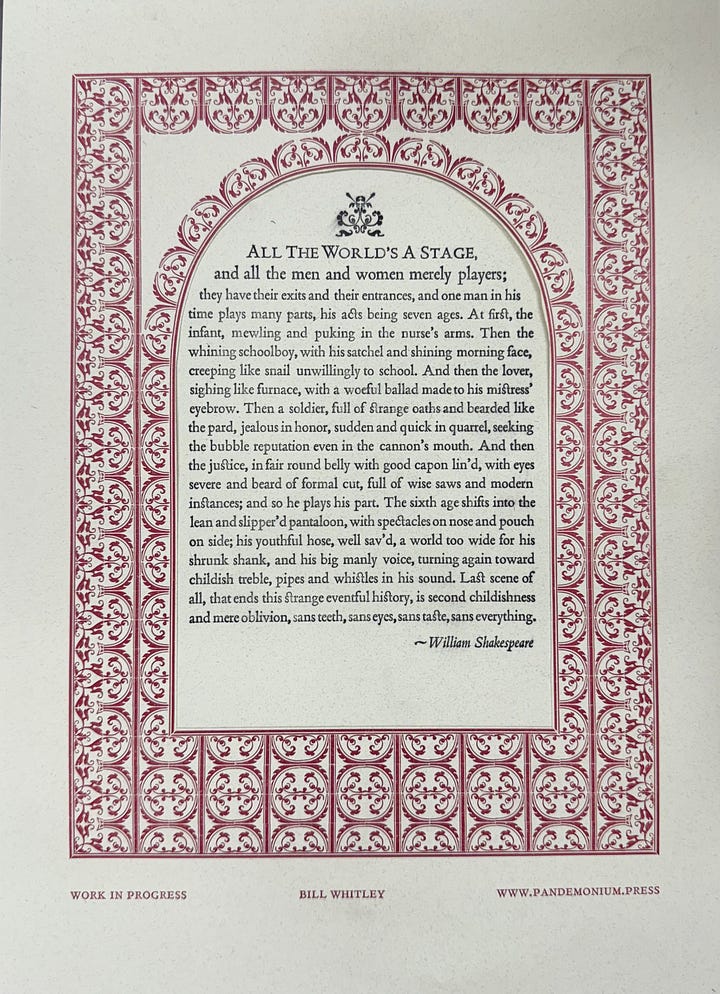

Bill started letterpress printing more than 50 years ago, and his Pandemonium Press studio is a perfect reflection of his commitment to craft. In his remarkably attractive and pristine workshop, he has whittled his collection of presses down to three; two antique platen presses, and a very rare 1937 Vandercook 317 cylinder proof press. There, Bill uses scores of metal type founts to hand-set and print some of the most beautiful letterpress work I have ever seen.

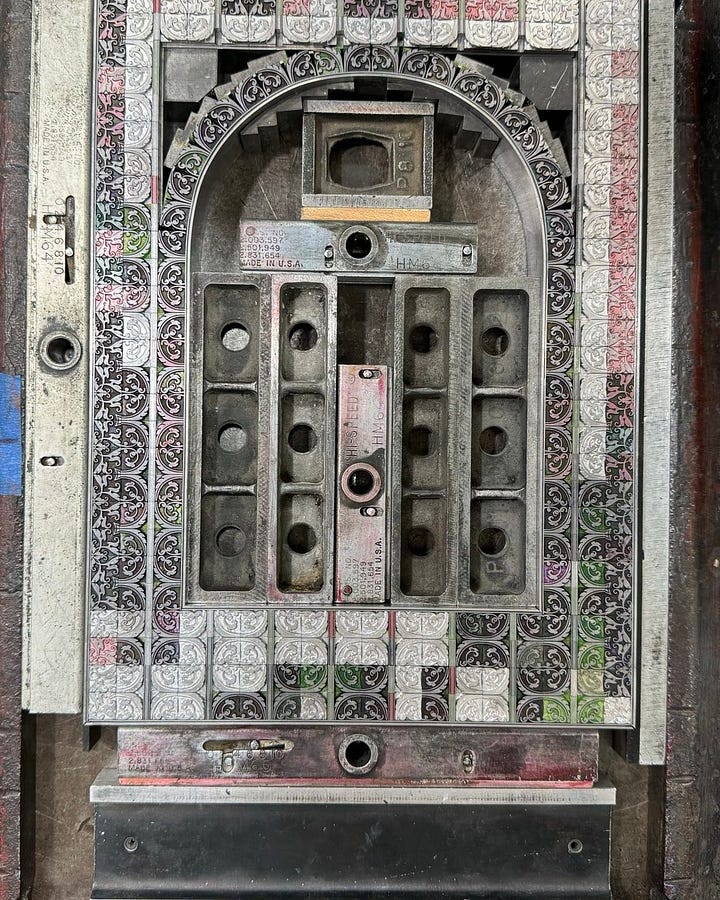

It turns out that about a decade ago, Bill and his friend Don Hildred had rescued three Miehle V-50 Vertical presses from a print shop in Denver. Ever since, these works of mid-century industrial art had been stored at Don’s farm outside of Fort Collins, Colorado. The Miehle V-50 is, to my mind, one of the greatest cylinder presses ever made. And because it takes up less floorspace than the similar presses (a function of its “vertical”-ness), I actually had room for two in my studio. Given all of this, how could I say “no” to Bill and Don?

So, last week, I made the trip to Fort Collins – a lovely small city at the foot of the Rocky Mountains – to visit Bill, Don and these presses. And thus the next stage of my private press adventure began.

Platen Press vs. Cylinder Press

Why would I be seeking out a cylinder press? After all, I had recently printed Master and Commander on a Heidelberg “Windmill” press – the Rolls Royce of platen presses. Well, it all comes down to how ink best makes its way to paper.

A platen or “clamshell” press uses a flat surface to lay – under heavy pressure – an entire sheet of paper against a flat bed of inked, raised type. When the two flat surfaces come together, ink is transferred from the type to the page in a single impression. This is precisely how Gutenberg’s first press worked, and remained a mainstay of printing well into the second half of the 20th century.

Similarly, a cylinder press also has type set on a flat bed. However, rather than pressing an entire piece of paper against the raised type, a cylinder press rolls the paper over the type. Only a small strip of the paper – a thin line across the width of the cylinder – is in contact with the type/ink at any given moment.

You can imagine how these two printing mechanisms differ by thinking of common kitchen tools. The action of a platen press is like pressing two cutting boards together, one on top of the other; contact is spread across the entirety of the two surfaces. In contrast, a cylinder press is like a moving a rolling pin across a cutting board. At any given moment, only a very small line of contact exists between the cylindrical pin and the flat board.

Which would you prefer to use for preparing a pie crust? Putting the dough between two cutting boards and pressing really, really hard? Or using a rolling pin to shape and spread the dough a bit at a time? Sure, the former can lead to a thin sheet of dough, but most of us prefer to roll it out.

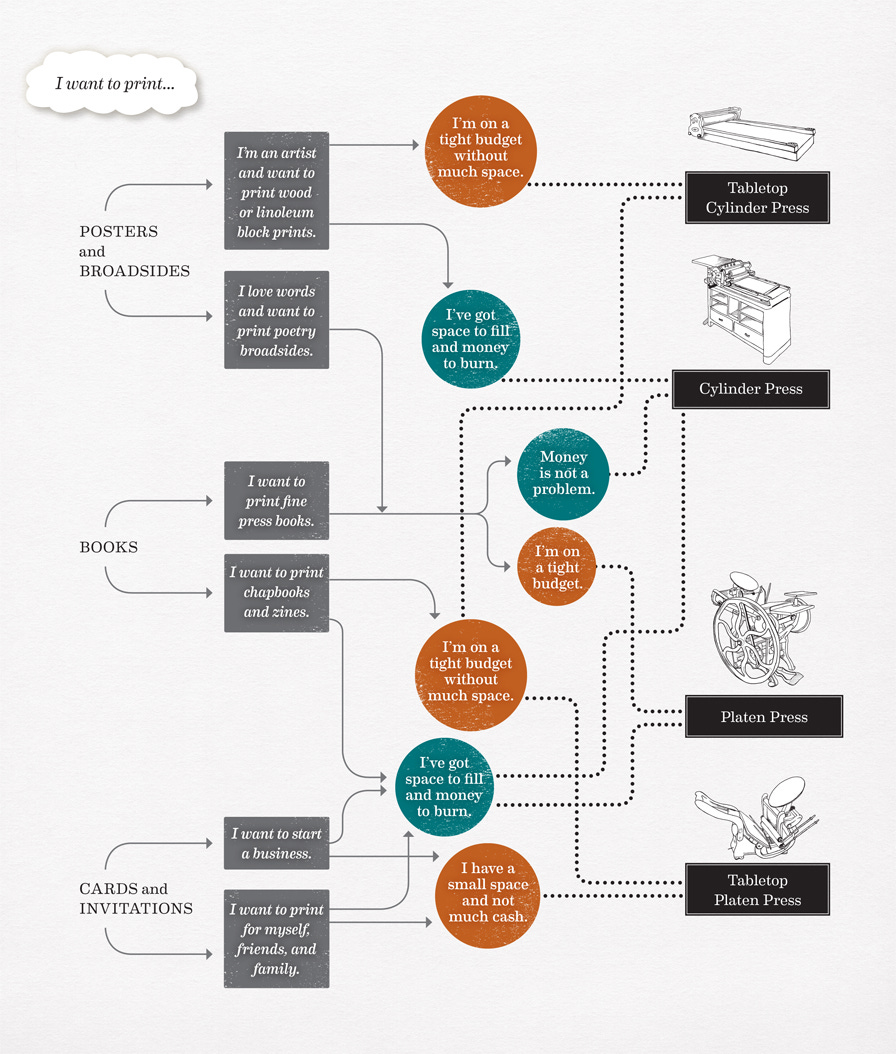

Although an imperfect analogy, this summarizes some of differences between a platen press and a cylinder press. Careful press operation can lead to excellent results using a platen press – as I hope I have accomplished with Master and Commander. However, the advantages of a cylinder press are undeniable. Indeed, as you can see in “Choosing the Right Press” on Letterpress Commons (below), when it comes to seeking the ultimate quality in letterpress printing, all roads lead to cylinder presses.

From Flat to Round: The Development of the Cylinder Press

Although wonderful results can be achieved with platen presses – and have been from Gutenberg until today – cylinder presses remain the gold standard of letterpress, especially for books, newspapers, zines, and other text-heavy printing.

So, you may ask, why doesn’t everyone, use cylinder presses? Well, there are many reasons. First, and foremost, tradition. For centuries, platen presses were the way in which printing was done. Every single piece of print in the Western world for nearly four centuries was done on a platen press.

The first cylinder flatbed press was not invented until the early 19th century. After the death of his father, 16-year-old Friedrich Koenig (1774-1833) was forced to apprentice himself to a printer to support his family. Hating the hard, repetitive work of printing, he turned his mind to how the power of steam – the engine of the Industrial Revolution in England – might be used to ease production. Finding little interest in or support for his ideas in Germany, Koenig migrated to London where, after building wooden prototype of his press, he partnered with a fellow German émigré, engineer Andreas Friedrich Bauer (1783-1860) to invent a working cylinder press.

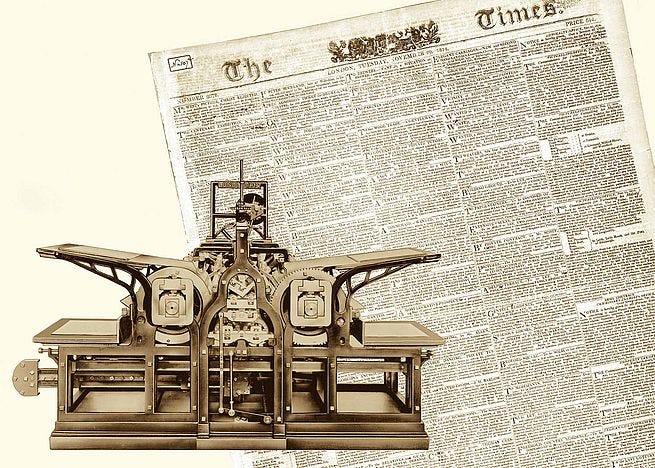

On November 29, 1814, The Times of London was printed using the first fully-realized Koenig-Bauer press. From that day until this, the Koenig & Bauer Company has been at the forefront of printing technologies.

As with other technologies of the Industrial Revolution, the adoption of steam-operated presses was not without its social costs. These mechanized steam presses put many of workers out of a job. At the same time, however, it made printed matter much cheaper and more easily accessible to a public that was increasing literate and eager for things to read. Indeed, it could be argued that without the mechanization of printing – and the inexpensive newspapers, magazines, and books that it produced – much of the Euro-American literature of the 19th century would never have been published. This is especially true of authors such as Charles Dickens whose work was often published in magazines and serially as some of the first “pulp” paperbacks. In fact, the term “pulp fiction” comes from the new use of tree pulp – instead of cotton, linen our other costly fibers – to make the massive amount of paper required by the mechanization of printing.

Cylinder Proof Presses

From my perspective, the future of Ampersand Book Studio requires moving from the the Heidelberg Windmill press – about which I have written previously – to a cylinder press. But which one?

Today, the vast majority of letterpress printing is limited to one-page broadsides, artwork, and very short publications. Across the world, a renaissance of such artisanal printing has been taking place. For such production, the press of choice has become cylinder proof presses.

Within the printing industry, a proof press was exactly that; a small press for quickly and easily printing a “proof” – a trial impression of a page used to proofread and make changes prior to printing on a larger, production press. Although several companies offered such presses, those made by Vandercook & Sons were the most widely used and are the most widely sought today. Starting in 1909, Vandercook offered over 60 models, making countless improvements over 75 years. Nearly all, however, shared a common foundation: paper carried by a geared cylinder would roll over inked type that rested on a flat surface.

Although wonderful in their own right, proof presses come with some significant limitations. Because they were designed for printing single copies to be used for proofreading, they are (mostly) fed and operated by hand. For each impression, the operator must insert the blank paper into the grippers on the cylinder and, using a lever, roll it across the type. Many even require manual application of ink using a brayer or roller. This means that each impression is relatively slow and requires several manual steps. Compared to an automated press, they are extremely slow and labor-intensive.

For most letterpress artisans today, none of these limitations are particularly significant. After all, if you are printing an edition of 100 posters or broadsides, taking a few hours to print them is just fine. And the simplicity of these presses combines with all of the benefits of a cylinder press to make them perfect for such small-scale production. As a result, in recent years, demand for these presses has far outpaced demand. This means that the price for a good Vandercook can easily exceed $10,000. Even those that require significant restoration can cost thousands.

Despite all of the benefits of proof presses to many artisan printers, they are simply not practical for the production of limited edition books. Printing just 200 copies of Master and Commander, for example, required over 75,000 press impressions. Imagine how long it would take to hand-feed, ink, crank, and remove each sheet of paper for each and every impression. At best, I could print, perhaps, 120 sheets per hour, more likely, fewer. On the automatic Heidelberg Windmill, I was able to print up to ten times that number. Plus, I did not develop a strange Popeye-effect on the one arm used to crank the press.

Miehle Vertical Presses

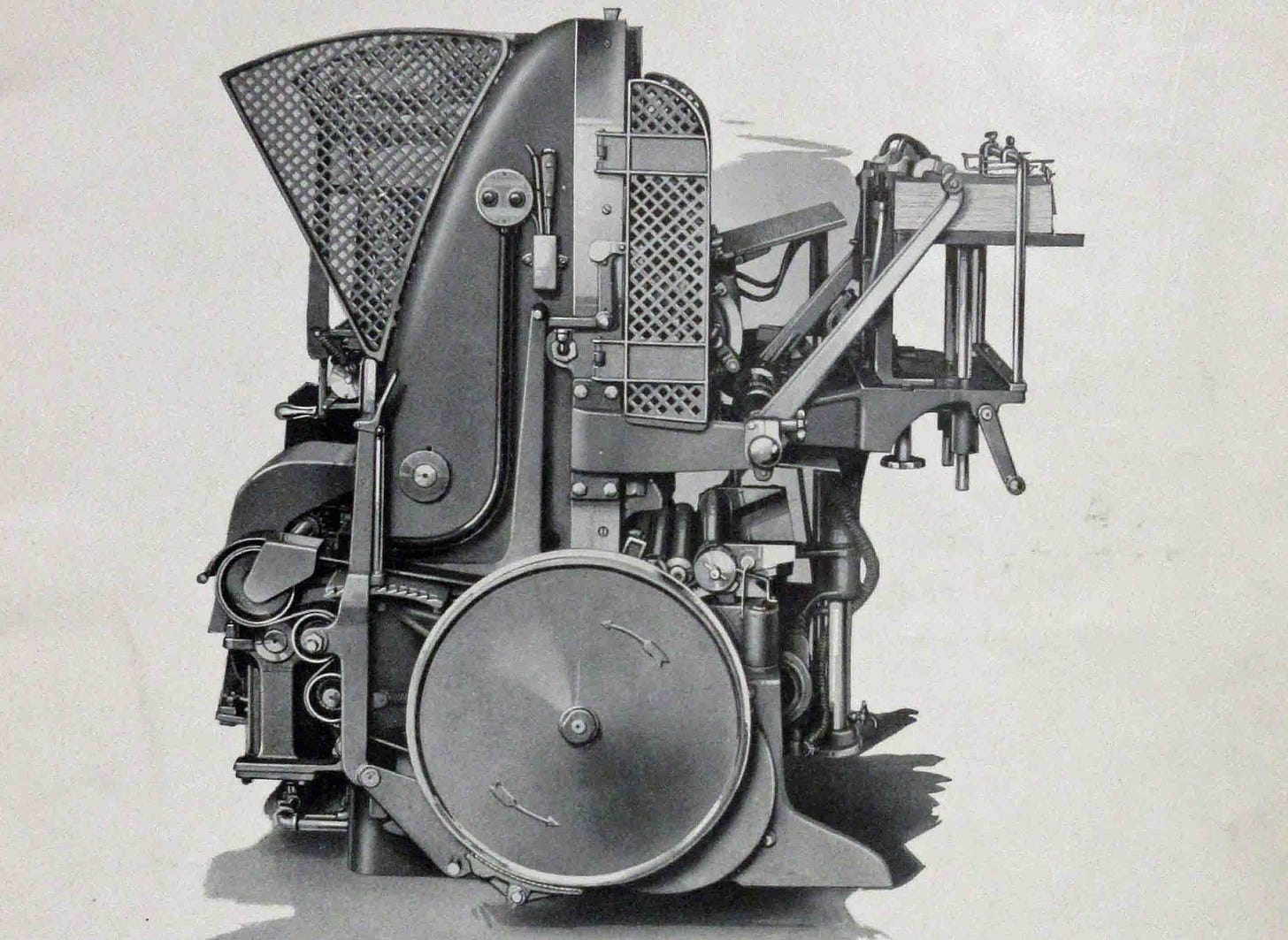

The Miehle Vertical press is to cylinder presses what the Heidelberg Windmill press is to platen presses… a precise and robust printing machine that became the standard in the mid-20th century. They were the cornerstone of many a printshop, from main street to industrial parks to the fields of Europe where Allied forces parachuted them in to print everything from maps to propaganda during World War II.

Robert Miehle, born in the Midwest in 1860, worked as a pressman in his brother's print shop in Chicago. In 1884 he patented a two-revolution flat-bed cylinder press. About 1890 he founded the Miehle Printing Press & Manufacturing Co. to build the press. Once the Miehle was established, its domination of the flatbed cylinder press field never was threatened. In 1920, Milwaukee press designer, Edward Chesire, originated the vertical concept in a cylinder press. But after building only three of the presses, he sold his rights to Miehle the following year. Certain changes were made in the design by Miehle engineer Craig Spichter. On Oct. 10, 1921, the press made its debut.

The Miehle V-36 was a revolutionary design. First, by rotating the printing bed from horizontal to vertical, it was much more compact than other presses, taking up less floor space and allowing for greater efficiency in the printshop. Second, rather than having the cylinder do all of the movement of paper over the print bed, both the cylinder and the print bed move, each doing half of the work. This meant that printing could be faster, initially 3600 sheets per hour (hence V36).

Beyond the aesthetic changes to the “fins” of the press – each an aesthetic expression of its era – subsequent iterations increased the maximum speed at which printing could take place. The V45 (released in 1931) could handle 4500 sheets per hour, and the V50 (released in 1940) churned our 5000.

Although each generation of the Miehle underwent incremental improvements, their fundamental operation has remained the same: the vacuum and fans of an automatic feed system place sheet of paper onto a cylinder… rollers transfer ink from a fountain to the raised type… the cylinder rolls the paper across the type… and the printed sheet is placed on a delivery tray or “table.”

By the 1970s, the final Miele Vertical press – the V-50X – was introduced. Primarily aimed at the check printing industry, it allowed banks to customize names, addresses and account numbers on up to 60,000 checks per hour. Although roughly the same as its predecessors, it had a boxier, more “modern” sheet metal design – and to my eye, was much poorer for it.

For many decades, Miehle Vertical presses were a mainstay of printers across the United States and beyond. A version of them was manufactured in England, and today, I know printers in Mexico and Argentina who are using them. Our friends at Betts Printing in Tucson – where I actually printed Master and Commander – use the V50 in their logo, and Eric Doyle, proprietor of Betts, first learned how to print on the one that was on their shop floor for decades.

All of this is to say that when Bill offered me not one, but three of these wonderful presses, I could hardly pass up the opportunity

Awakening Sleeping Presses

For the last decade, the three V50s have been in storage at the family farm of renaissance man Don Hildred and his equally-skilled wife, Ann Baker. Don was born and raised on this 20-acre farm in the shadow of the Rockies. He has primarily been a commercial machinist, but has sidelines in welding, high-pressure air systems, scuba equipment, blacksmithing, printing, and helicopter repair. As you might imagine, he uses all of these skills on the farm. Today, the farm is home to a flock of 50 sheep, three llamas, laying chickens (which roam the farm, laying eggs in unusual places), a mouse-hunting cat, and, most eclectic of all, a group of equally diverse people.

Over the three days of my visit, the farm was a hive of human activity. Darryl (a skilled carpenter who spends nine months every year living on a boat in Barcelona’s harbor) and Ro (a Uruguayan woman who has lived across Europe for twenty years) were busy upgrading electrical systems in the barn… Alex, a former professional cyclist and beekeeper, was helping to finish a production woodworking facility where he will process tens of thousands of board feet of plantation teak that he is importing from Costa Rica… Don and his brothers, Steve and John, were building a crane that they would use to lift and convert the drum of a cement mixer truck into a massive sawdust collection container… Ann hunted in “all the usual places” for eggs laid by the chickens… and we excavated three Miehle V-50 Vertical presses from a trailer where they have been in storage.

Nearly a decade ago, Don, Steve, John and Bill had rescued the presses from a Denver printer who, himself, had rescued them from being scrapped ten years before that. For a while, both Don and Bill thought that they would find a use for them in their respective print shops. But as these things go, they sat, loved and protected, but unused. Until last week.

Using two of Don’s fork lifts – Sully and Frankenfork – we moved palettes of other heavy equipment from in front of presses. Don then moved each of the 3200-pound/1450-kilo presses into the busy barn. Despite the dust and grime of nearly 20 years of storage, not to mention the ink and grease from their operating days, the presses started right up.

Later this summer, Don and Bill will truck these presses to a shipping depot where they will begin their journey to my Tucson studio. Will they need a good cleaning? Yes. Do I need to replace some of the rubber vacuum hoses that have become brittle with age? Sure. But after a bit of TLC, they will be just as capable of exceedingly high quality printing as the day they were first delivered from the Miehle factory.

This is a huge development of Ampersand Book Studio. It will allow me to take the next step in the journey of producing fine press books. I am exceedingly grateful to Bill and Don for their friendship and generosity, and to Eric from encouraging me (and agreeing to be my on-call mentor and coach for when I run into the inevitable challenges of learning a new press).

For now, however, it is time to get back to binding Master and Commander. After all, I will need the space occupied by the books for the new presses.

There is a fascinating visual resonance between your ampersand logo and the Miehle image.