When I was growing up, there was a public television show for children called The Big Blue Marble. Highlighting cultures from around the world, it took inspiration from the 1972 photograph of the earth taken aboard the Apollo 17 spacecraft.

Jack Aubrey and Stephen Maturin would have marveled at this perspective of the planet that took them months and years to traverse. However, for centuries before we had this view of our home, the swirling patterns of nature inspired artists and craftspeople across the globe to create what we now call marbled paper.

For the covers of our Anchor Edition of Master and Commander, it seemed natural to choose such marbled paper. Not only was marbled paper central to the aesthetics of late 18th century English bookbinding, but it also seems particularly appropriate for a nautical adventure. Marbled paper captures movement, almost like currents and tides brought to paper.

Let’s explore marbled paper from an historical perspective. I would also like to introduce Jemma Lewis, the wonderful artist who has created the marbled paper for our Anchor Edition.

A Global Artform

Prior to its introduction to Europe at the end of the 16th century, numerous cultures seem to have developed the technique independently with Japanese shumigashi and Turkish Ebru being the most important.

Japanese Suminagashi

The Japanese may have been the first culture to develop a form of paper marbling: suminagashi or “floating ink.”

The Metropolitan Museum notes that suminagashi “existed well before the commonly known European, Turkish, or Persian methods. Currently the oldest suminagashi sample dates from the twelfth century, although references to the technique go back to as early as 825–880 c.e. in the poetry of Shigeharu.” Suminagashi is not simply an artistic practice, but a spiritual one as well; it is sometimes used by Buddhist monks as a meditation technique in which movement and gesture reflect natural patterns.

In this video, the late Tadao Fukada demonstrates the traditional Japanese techniques and processes.

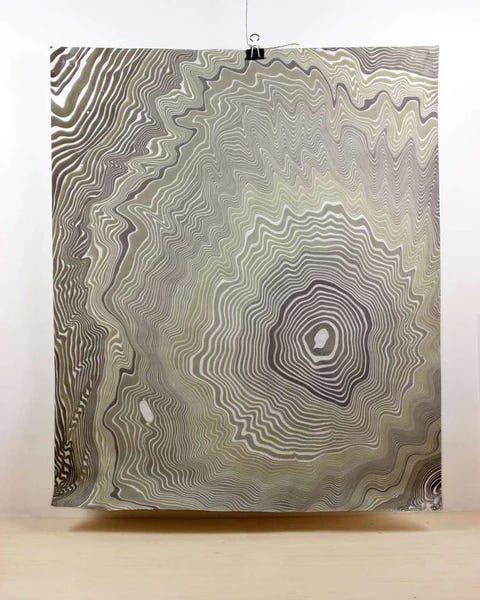

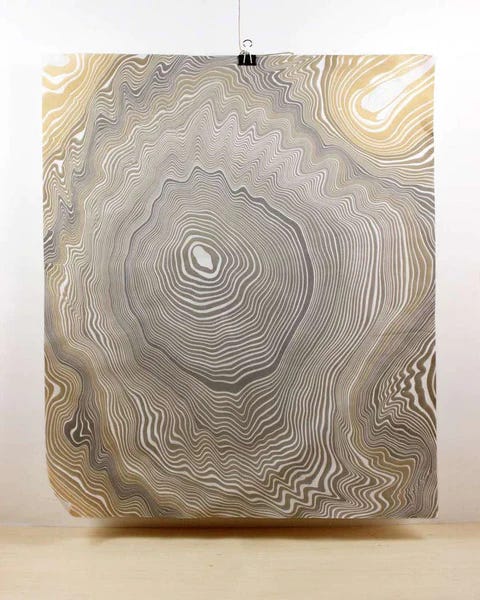

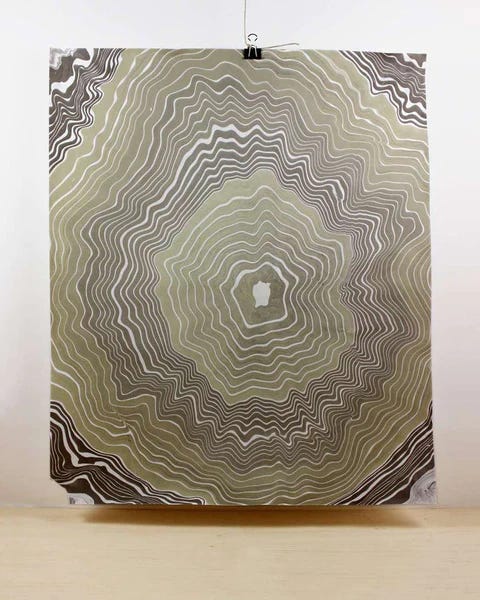

Suminagashi designs are naturalistic, like tree rings or ripples in water after a heron catches a fish. Although not appropriate to our 18th-century English binding on a book of nautical fiction, suminagashi patterns are also reminiscent of topographic maps, as can be seen in these wonderful contemporary examples by Crystal Shaulis (https://lakemichiganbookpress.com/blogs/news/new-suminagashi-prints):

Persian and Ottoman Ebru

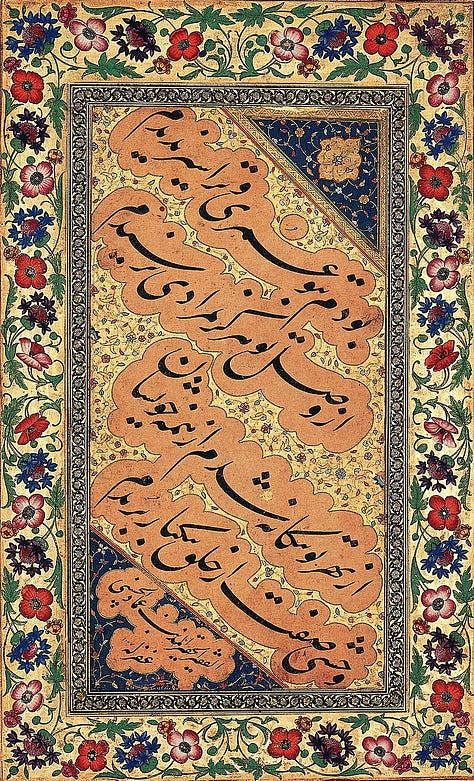

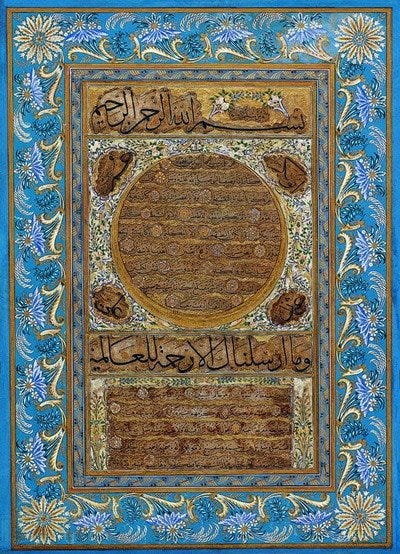

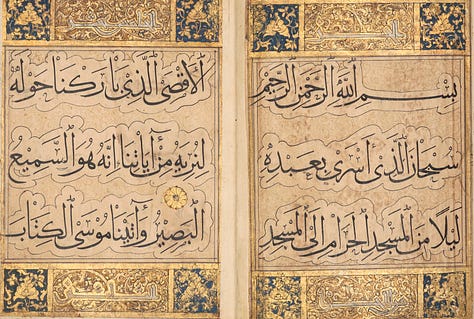

Within many Islamic traditions, aniconism – the prohibition of images of sentient beings – has meant that more abstract decorative arts were cultivated. Complex geometric and floral patterns became central to architecture, while calligraphy was developed into a high art.

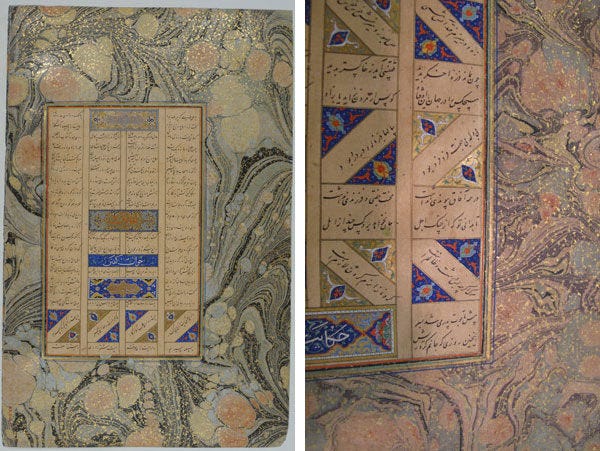

It is within this context that marbled paper became central to Persian and Ottomoan decorative arts. Although it is not entirely clear whether paper marbling arrived in Persia and Turkey over Silk Road trade routes or was developed autonomously, by the late 15th century ebru paper marbling was being used throughout the region. Rather than a separate aesthetic expression, ebru was primarily used to frame and/or highlight Arabic calligraphy. Yana van Dyke, a conservator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, discussed some of the remarkable examples housed in the museum’s collections:

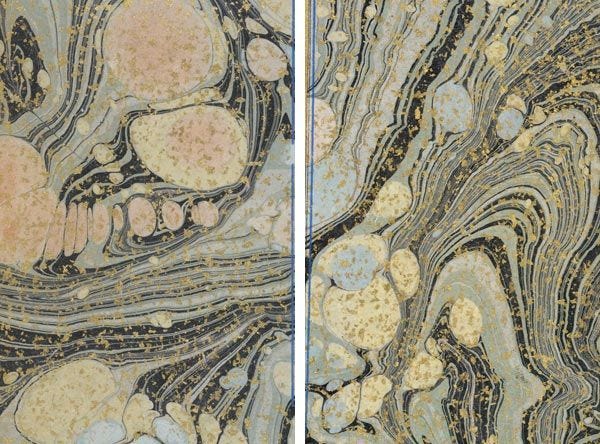

Marbleized paper, known as ebru, which translates to "the art of clouds" ("cloud" is ebr in Turkish and abri in Persian), has a long tradition in Turkey and came to be much favored for calligraphic work. The marbling used for the outer borders… is stunning in its variety of shapes and magnificent display of both organic and inorganic colors and bold rhythms. The patterns are the result of color floated on the marble bath (a viscous solution of carrageenan moss/algae) and then carefully transferred to the surface of the paper. Delicious and intense pink, orange, yellow, blue, and orange hues swirl and flow into and around each other to create blossoming flowers, traditional combed peacocks and getgels (a series of combed parallel lines bisected by another series of combed parallel lines that run in the opposite direction), and sprinkled and speckled stone. (https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/ruminations/2015/marbled-paper)

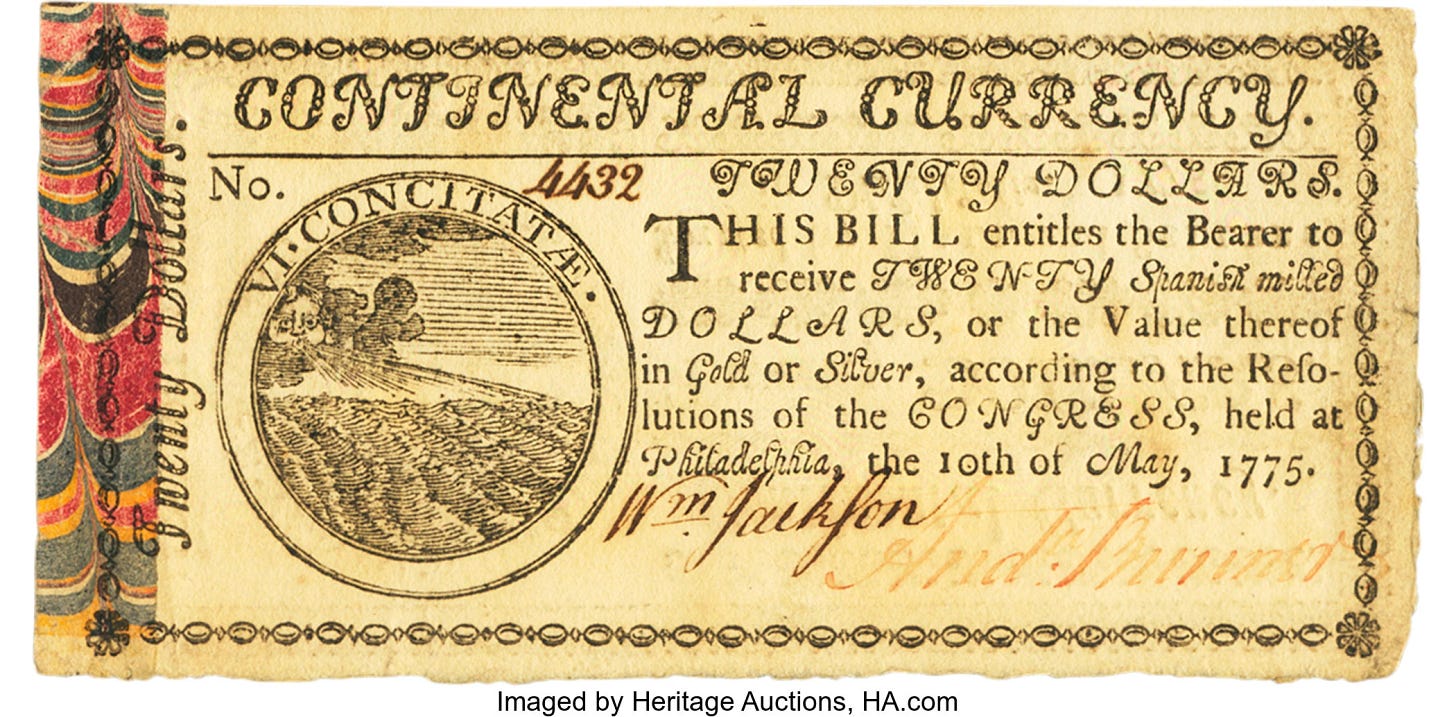

In addition to its ornamental uses, marbled paper was also used in government and legal documents to help prevent the creation of forged or altered documents. For example, when multiple copies of a document were written on a single sheet of marbled paper, they could be cut apart and distributed. If an altered or forged copy emerged, it could then be compared to another copy. Because each sheet was unique in pattern and pigment, a forged copy could never stand up to such scrutiny.

Over time, ebru increasingly developed into an artform that stands on its own, rather than only as a frame for the written word. In Turkey today, a group of dedicated ebru artists continues to look to tradition and combine it with more contemporary elements. Bayt Al Fann – Arabic for “art house” – is an international collaborative of artists who are “driven by a vision of a vibrant and thriving future for Islamic art, heritage, and culture. We launched the project in November 2021, with the dream to create a global home where artists, creatives, and communities come together and co-create the future of this timeless art. We welcome everyone, Muslim and non-Muslim alike, to explore the past, present and future of Islamic art, culture and heritage together.” As part of their online presence, they highlight several contemporary artists working in the ebru tradition.

European Marbling

By the late 16th century, travelers to the Middle East had brought back examples of marbled paper to Europe. Viewed as much from a mathematical and scientific as from an artistic point of view, within a short time, techniques and designs were being shared across the continent, primarily through technical accounts such as those of Gerhard ter Brugghen (Verlichtery kunst-boeck, Holland, 1616), Athanasius Kircher (Ars Magna Lucis et Umbræ, Rome, 1646), and Daniel Schwenter (Delicæ Physico-Mathematicæ, Germany, 1671).

While elements of the Persian and Ottoman designs were adopted, throughout Europe a wide variety of techniques and patterns were developed, often associated with specific publishing regions, particularly in Holland, England, France, Italy, and Germany.

Beginning in 1695, the Bank of England used marbled paper in some of its banknotes. However, it was discovered that counterfeiter William Chaloner was successfully forging similar notes – an offense for which he was prosecuted by the Royal Mint’s Warden, Sir Isaac Newton, and hanged in 1699. English marbled paper also made its way across the pond where Benjamin Frankin used it to print the Continental Congress’ $20 banknote in 1775.

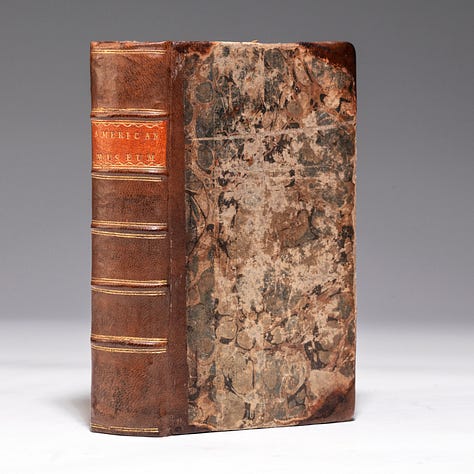

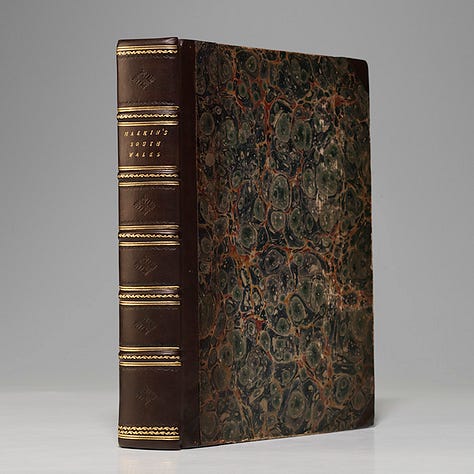

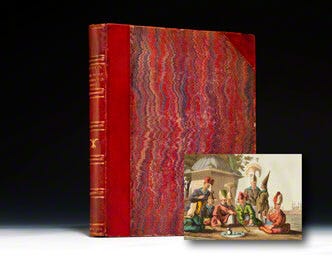

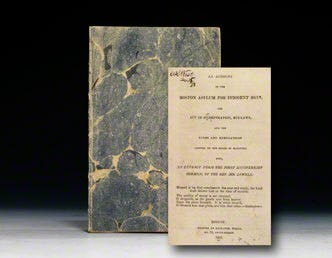

More common than its use for currency, however, was the use of marbled paper as a decorative element in the production of books, especially in England and the United States during the 18th and 19th centuries. The most well-preserved marbled papers are those used as the endpapers – the decorative pages at the start and end of a book. As they have not been exposed to more than 200 years of light, dust and handling, endpapers tend to be better preserved than the marbled paper used on covers. However, it is possible to see its use on the covers of countless books from the period.

As aesthetically pleasing as these marbled-paper covers – or “boards” in bookbinding parlance – are, in some ways they were a somewhat cheaper alternative to the full-leather bindings of the era. At a time when publishing (and literacy) was rapidly expanding, alternatives to leather were sought. Goatskin, arguably the best leather for bookbinding, was relatively scarce, and mostly imported from warmer climes than that of the British Isles. In the half-leather bindings seen above, leather is reserved for the high-wear parts of the book: the spine, hinge and corners. Leather serves as a frame for the decorative marbled paper. It is within this tradition that we locate our Anchor Edition.

Jemma Lewis Marbling & Design

For Master and Commander, I wanted something that conveyed the movement of the sea, was within the English marbling tradition, yet also had hints of modernity. I found exactly what I was seeking in the remarkable work of Jemma Lewis of Wiltshire, England. Jemma creates some of the finest handmade marbled paper available. I asked her how she started with marbling.

My route in to marbling began with my job at Period Bookbinders/Chivers Period Bookbinders where I worked for several years and where the opportunity arose to learn paper marbling with Ann Muir who was looking to sell her marbling business. I was sent to train with a view to the bookbinders buying her business but unfortunately before all this happened, Ann who was very ill at the time, passed away and the bookbinders went in to administration. Having spend many months already learning this wonderful craft I took the plunge and set up a studio in my back garden fully assisted by my fantastic Dad who worked with me here for 7 years before retiring. I have such a love for colour and pattern and find inspiration everywhere, I have the biggest stash of magazines which I'm always taking cuttings from as inspiration and new colour-ways ideas.

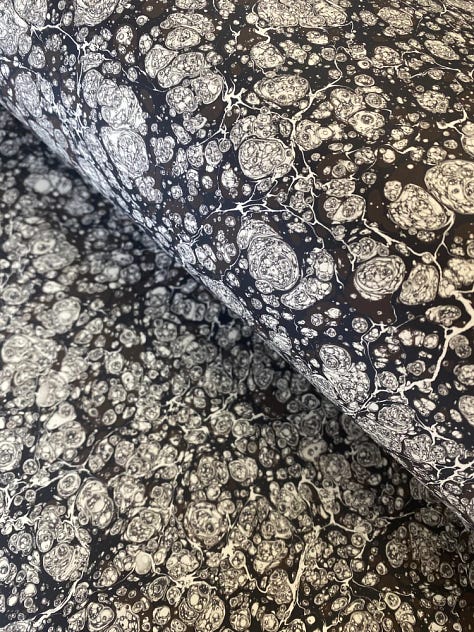

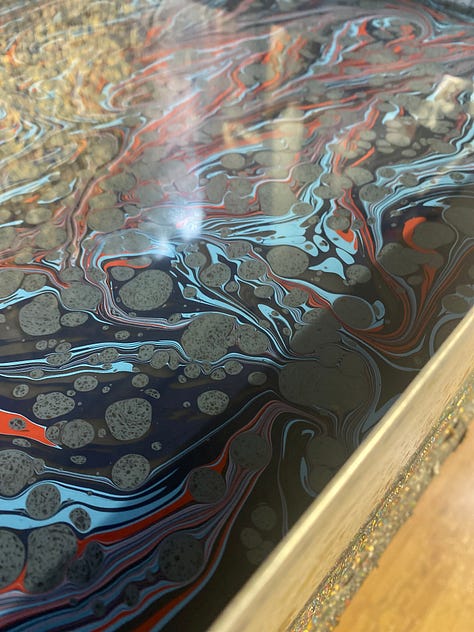

I was particularly captivated by Jemma’s “Stormont” pattern which she offers in various colorways. For me, this design captures the energy and movement of sea water. I can see currents and waves and even the foam created by the bow wave of a ship with a strong tailwind.

Jemma notes that it is also particularly appropriate for the period of Master and Commander:

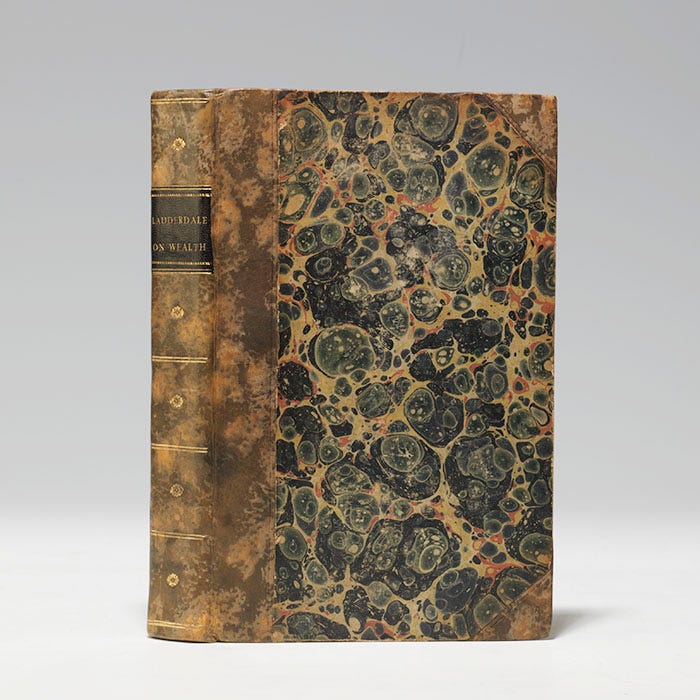

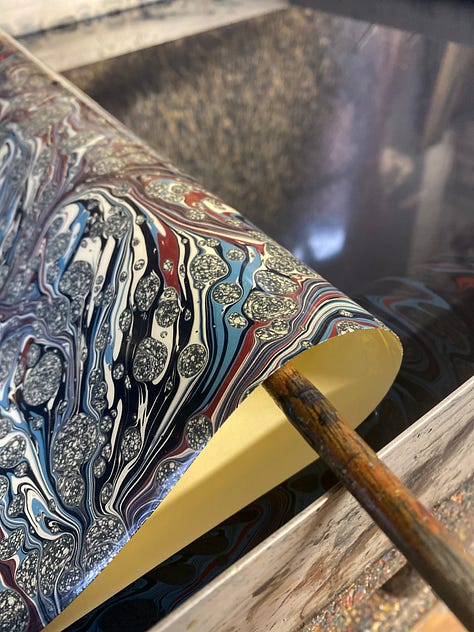

The Stormont pattern was said to have been first used in Dublin in 1750 (Stormont is the name of a district in Belfast, Northern Ireland). The main characteristic of the Stormont design is that the spots have a lacy, bubble effect. This is created by adding drops of oil and turpentine to the colour you wish to have this effect. The addition of these two liquids to the paint does make this a pattern that is particularly hard to keep consistent, but of course with marbling being fairly organic anyway we enjoy the variation as it adds to the handmade charm of these sheets, making each one truly unique. As the degree of laciness can change depending upon how much the paint and chemicals get mixed we work with two separate pots - one that is full of the paint mix as it is, to the second pot we decant a tablespoon of paint at a time and to this we add the drops of oil and turpentine meaning we are only combining the mix for a small portion at the time. This not only aids consistency but it also avoids unnecessary wastage.

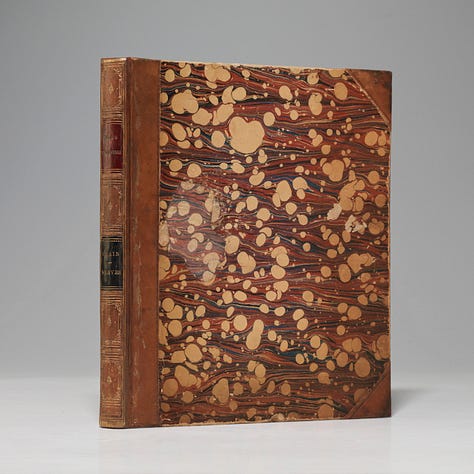

This 1804 copy of An Inquiry into the Nature and Origin of Public Wealth, and into the Means and Causes of Its Increase by James Maitland, Earl of Lauderdale, features the bubble effect of the Stormont pattern that Jemma describes.

Given its Dublin origins, one can imagine Stephen Maturin, as a student at Trinity College, reading many books that featured Stormont mabled paper.

While the designs for Jemma’s marbled paper may be traditional, she also seeks to “modernize” them in subtle ways.

The traditional designs and patterns still form the basis of many of the hand marbled papers myself and many other paper marblers still produce today. I personally love to modernise these by combining the traditional designs with a more contemporary palette, including turquoise and pink for example in lieu of darker shades like browns and greys.

With a wish for blues and grays to be dominant in our papers, Jemma set out to bring the project to fruition. Happily, she shared some photos of the process of producing the very sheets we are using.

This video of Jemma working provides a glimpse into her creative process.

I also love to work on coloured base papers and incorporate lots of metallic paints. I love to spend as much time as we can dedicated to making 'one-of-a-kind' papers - we don't really have anything specific in mind when we have a session, we love to experiment and play and let the magic unfold naturally!

While not appropriate to our historically-inspired volume, I adore the bold, new palettes that Jemma is also creating using historic patterns.

Other Workshop Updates

Production continues apace. We have been tipping in the illustrations. I am delighted by the quality of reproduction of Carlos Kirovsky’s artwork we achieved using giclée printing on light Japanese paper (which was discussed in a previous post). Despite the time needed to trim and tip in over 2000 illustrations by hand, it was definitely the right decision.

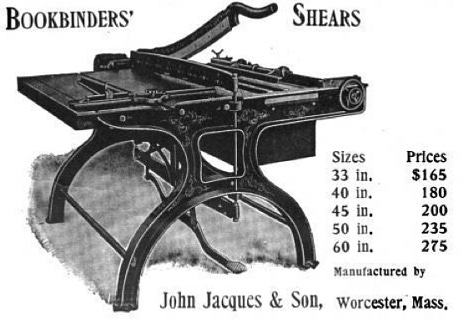

We are also preparing the boards in preparation for attaching them to our books. Among other things, this meant adding yet another wonderful tool to the expanding workshop: a new (to me) John Jacques & Sons board shear made in the early 1920s. Used to cut the heavy binders board out of which the hard covers of a book are made, this is the last major piece of equipment that I had been seeking. However, not only are they no longer made to the same standard as those made a century ago (although the German bookbinders supply company Schmedt comes close), it is a beast. Made entirely of cast iron, it weighs nearly half a ton. Needless to say, moving such a behemoth into my studio was not without its challenges. However, it is now in place and being used to precisely trim boards to fit each book. Book conservator Jeff Peachey has a wonderful blog post about Jacques board shears.

Speaking of covers, the wood from HMS Victory is nearing delivery. It has been removed from Victory and is ready to ship. It has been a very long saga, but for now, here is the wood as it sits at the shipyard in Portsmouth.

That’s it for now. Another (long) post is in the works about the process of securing this historic wood. It will have to wait, however, until the wood actually arrives here at our workshop in a few weeks. Until then, fair winds and following seas.

One of the most interesting and informative updates I have ever had the pleasure of reading. I am on tenterhooks (although I don't think that is a nautical term) for the final reveal.