Ink on paper is almost certainly the most revolutionary communications technology in history – one that may only be eclipsed by the digital world. Many of us know the history of paper from its invention more than 2000 years ago by an official in the Chinese court to its introduction in Europe a thousand years later to wood-pulp papers of today. But what about the other half of the equation? What about ink?

Ink: The Early History

Ink, in its most basic form, has been invented and re-invented in cultures many times. At its most basic level ink is just a pigment carried by a medium, almost always water prior to Gutenberg. When applied to a surface the medium dries, leaving the pigment behind in the form of an image and/or writing. In Egypt, ink was applied to papyrus from at least 2600BCE. In China, ink production goes back to the neolithic period 4,000 years ago. And in both China and Japan, there are still people manufacturing ink using the same techniques as were used many hundreds of years ago.

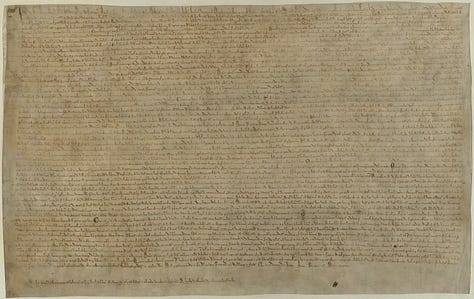

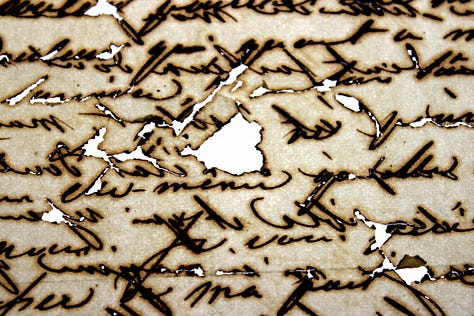

Globally, most traditional inks – including that shown being made in the remarkable video above – use soot as the pigment. However, in Europe iron gall ink was predominant from the 5th through 19th centuries. It is what was used on everything from medieval manuscripts and the Magna Carta to the (fictional) letters Jack sent home to Sophie. Made using iron salts and tannins derived from gall (growths on oak and other deciduous trees), over time, its dark purplish-black would shift to being a brown, almost rust-colored, tone. Unfortunately, it was also very acidic and could slowly eat away at paper, leading to extensive damage or loss of writing over time.

Press Ink

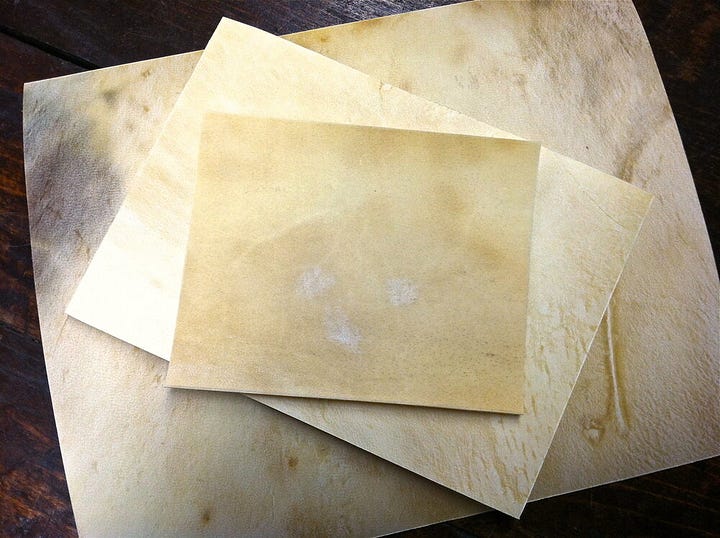

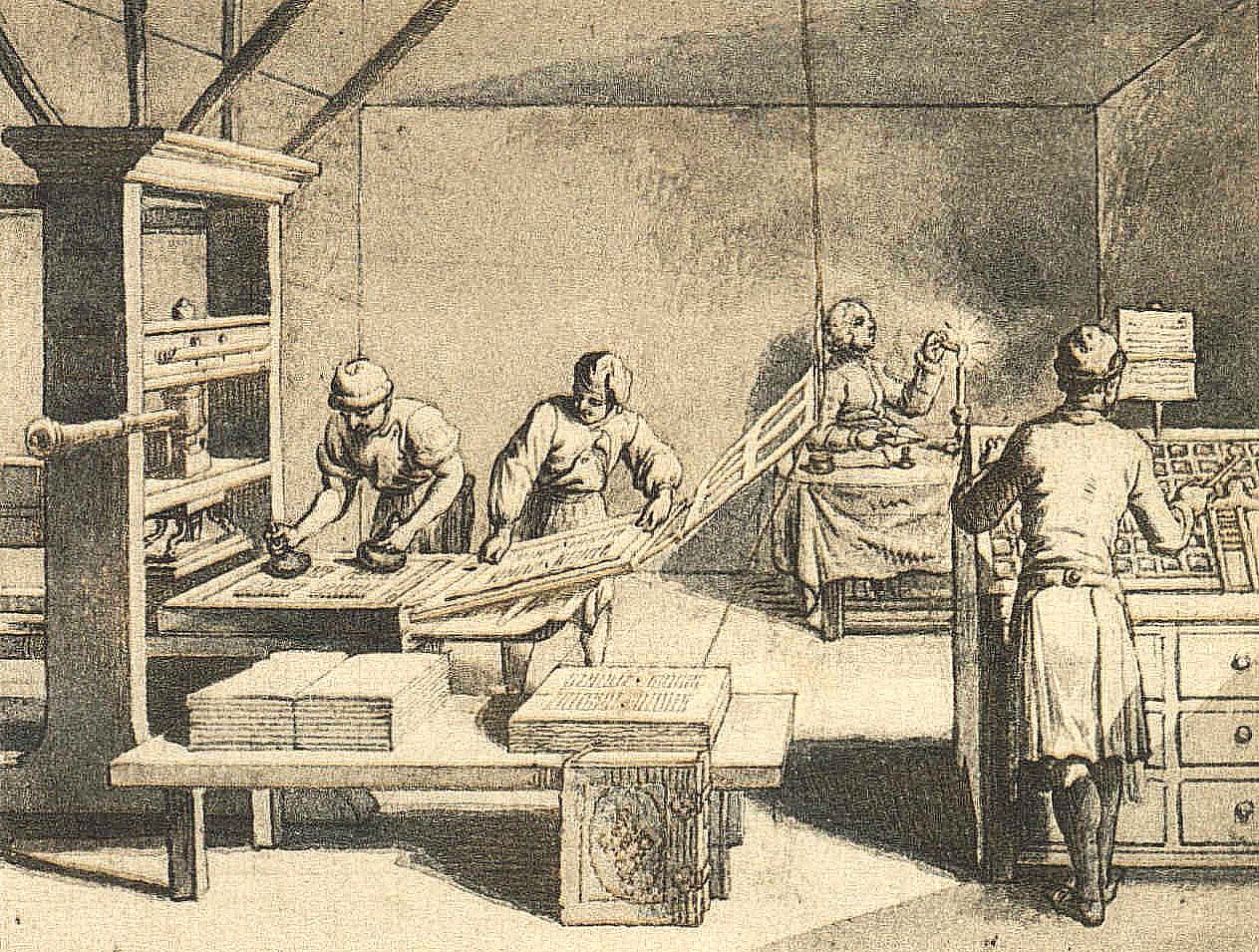

While Gutenberg’s press brought with it a revolution in knowledge and accessibility, it also necessitated a revolution in the media on which and with which printing took place. Prior to his moveable type press, almost all documents and books in Europe written thin parchment or vellum sheets. Contrary to the common use of the terms today, traditional parchment and vellum are the specially tanned and hand-scraped hide of an animal. Their production is both labor intensive and limited; the supply of vellum was limited to the number of sheep, cows, pigs, and sometimes wild animals that were slaughtered for meat. They were, in essence, a byproduct of food production. This was fine when books were largely produced in very limited quantities by scribes hand lettering each page in a scriptorium.

With the introduction of the printing press, however, the potential for the production of books increased exponentially. This led to an increased demand for paper. Indeed, when Gutenberg printed his famous edition of the Bible, only about 25% of the copies were printed on calf vellum, each requiring the skins of about 170 animals. The remaining 75% of copies were printed on paper. It is easy to see, then, how the invention of the printing press drove the move from vellum to paper.

Equally important, however, was the changes to ink necessitated by the invention of the moveable type press. Instead of dipping a pen into a water-based ink in order to write an a few words, the press would print an entire page (or multiple pages) at once. Water-based inks applied to metal type would simply flow off the surface and/or dry very quickly. In order to combat this, Gutenberg developed a new form of ink. He replaced water as a medium for carrying pigment with oil. Oil’s thicker, more viscous nature meant that ink remained on the surface of the type, and allowed a longer open working time before drying. Indeed, oil-based inks do not “dry” per se. Instead, they cure through a process of oxidation, developing a hard surface that helps protect the pigment. It is the same process by which the oil-based paints of the Old Masters would harden. Although it takes longer for this curing process to solidify ink than when using a water-based ink, the thickness and viscosity of these inks were necessary for use on a press.

As I have mentioned previously, despite improvements and automation of certain processes, letterpress printing remains much the same as in Gutenberg’s workshop. A piece of paper is pressed against an inked relief plate thereby transferring ink to page. Letterpress printing today, then, requires the same characteristics as those developed in the 1430s: viscosity, a long or open working time, and saturated pigmentation. From the 15th century well into the 20th centuries, printing inks remained relatively unchanged; they were pigments suspended in oil (almost exclusively linseed oil derived from flax). Minor changes in formulation (such as the introduction of waxes and lubricants) did take place over those 500 years. For example, John Baskerville – the focus on our previous missive on 18th century typography – was renowned for depth of color in his ink, as well as their quick-dying traits; he probably added varnish, a material with which he was familiar through his manufacturing of Japanned decorative objects. But there is no question that Herr Gutenberg would recognize the the ink we use for letterpress printing today.

The final major change to letterpress inks was the modern replacement of the oil as a medium with rubber in some inks. Rather than curing through oxidation, like oil-based inks, rubber-based inks “dry” through absorption into the paper itself. Printers love these inks. They stay “open” on the press for days. That is, because they do not harden through oxidation (as oil-based inks do) nor dry through evaporation (as water-based inks do), they can be left on the rollers of the press for days without cleaning all of the ink out of the press. For readers, however, they are more problematic. On thinner paper with little absorption, rubber-based inks never really dry. That is what explains the inky fingers we (used to?) get when reading newspapers; rubber-based inks on thin newsprint meant that the ink never really dried and ended up on our fingers. But it meant that the absolutely massive, industrial presses of your city daily did not need to be fully cleaned of ink every single day. Like so many industrial developments, the benefits of rubber-based inks were more to the producer than the consumer.

In creating our edition of Master and Commander, we are certainly using papers that could handle and “dry” rubber-based inks. But we are committed to oil-based inks not that different than those developed by Gutenberg. Would most readers ever notice the difference? Probably not by the time they receive the book. However, the hard, shellac-like process of oxidation of oil-based inks means that they will hold up to generations of readers and many re-readings.

Are Soy-Based Inks Better for the Environment?

There is a perception that soy-based inks are more environmentally friendly than the alternatives. While this is certainly the case when compared to the petroleum-based inks of industrial-scale offset printing, for letterpress it is a different story. Both traditional letterpress inks and soy-based inks use oil as the medium for carrying pigment. The only real difference between them is the source of the oil. Most traditional letterpress ink uses linseed oil that is easily extracted from flaxseeds whose oil content is in the 40-45% range. By contrast, soybean seeds have 18-22% oil content that is extracted using commercial solvents. So, not only do you need more than double the seeds to make soybean oil (as well as more land, water, and chemical herbicides, pesticides, and fertilizers), you need more chemical solvents to extract it. Grind flaxseeds in a coffee mill and you will see the oil glisten. Grind soybeans and you will get a dry powder. Without getting too into the weeds of U.S. food politics, farm subsidies, the marketing/lobbying of agribusiness, and the industrialization of agriculture, suffice it to say that soy inks are more ecologically damaging than linseed-based ones. Plus they dry/oxidize much more slowly. You don’t want smeary pages, do you? So, we stick with the tried and true linseed oil inks that have been used for centuries.

Shades of Black

Finally, color. Anyone who has purchased a gallon of house paint knows that “white” is no more a single color than blue is. There are “cool” whites – usually featuring undertones of blues/greens – and “warm” whites – with red/brown/yellow undertones.

But black is black, right? Not according my my wise mother. At dinner the other night, she said of her wardrobe, “some black clothes make me look washed out, and others make me glow.” She is absolutely right. “Black” is no more a single color than “white” is.

For many months, I have obsessed over almost every element of our book. I have written about the search for the perfect paper for previous books and how it has been impacted by everything from climate change to supply chain issues. In planning and describing the different states of our edition of Master and Commander, I touted the wonderful papers we are using from two centuries-old European paper mills. Paper gets all of the glory. But without ink, paper is nothing more than potential.

In designing the book, I have, of course, considered color. Our two-color design incorporates black text (obviously) and blue titles, drop caps, and headers. The blue I have selected is a classic: Pantone 300. It is as close to the platonic shade of blue as you can come – not navy or sky, not the royal blue of the Union Jack, nor that clothing-catalog-favorite, “seafoam.” It is blue. [Only after selecting it for aesthetic reasons did I find out that it happens to be the official color of the flag of Scotland. Following gunroom etiquette, I will not discuss Scottish independence, Brexit, or the morass of issues that might have led to conflict between Jack and Stephen had they been here to witness current events.]

However, until it came time to actually order ink, I had not really considered the black. Black is, well, black. Indeed, almost all manufacturers of inks for letterpress only offer two black inks: one for mixing with other base inks to get the rainbow of colors in the Pantone charts, and one for printing “black.” I was all set to order one of these – Van Son Universal Printing Black from a venerable company that has been making printers’ inks for over 150 years – when I went I came up short. One black? But what tone of black is it?

That is when I turned to Cranfield Colour, a Wales-based company that still handcrafts paints and inks for artists. Like Van Son, they too have a long, rich history. But unlike other makers of letterpress ink who offer thousands of colors and shades, Cranfield offers just six colors… all of them black.

Cranfield understands what my mother knows when she looks in the mirror: there are various hues of black. So they offer six furnace carbon black inks, five of which have undertones of other pigments (green, orange, purple, blue, and powdered aluminum). With three of them in hand, on Friday I turned to the press to test them against my previous standard, Van Son Universal Printing Black.

From the first impression using the Cranfield Midnight Black Traditional Letterpress Ink (described as “black with a hint of deep blue”), I was delighted! Somehow, at least at the small scale of text, you do not notice any blue at all. But you do notice the depth of the black. It conjured up memories of a cold February night in 1974 in the Lakes District of England. The six-year-old me had been on a bus from London for what seemed to be endless hours. Well past my bedtime, the lone taxi driver in the nearest village drove away, plunging us into complete darkness. We were left at the unlit door of a small, country cottage, in total blackness. I had never been in such darkness before. It was only my knowledge the “the sky is blue” that could mitigate the blackness of that moment. Cranfield’s ink is like that. You know there is blue, but all you see is deep, dark black. I had found the ink for our book.

You can learn more about Cranfield’s continuing work to create such evocative colors in this great profile from Jackson’s, a wonderful UK-based art supply company.

Total Blackout

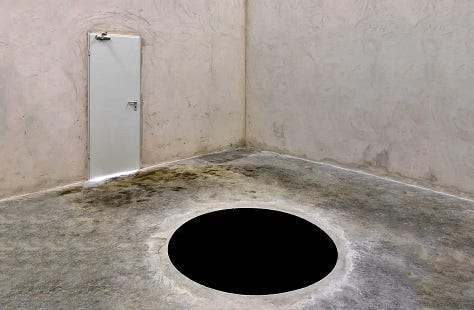

If you want to dive even deeper into the controversies of the color black, you may be interested in the case of Ventablack, a pigment invented in 2014 as the blackest pigment ever (absorbing 99.965% of all light). It is so dark that it gives the impression of a void and complete flatness. In 2016, renowned sculptor Anish Kapoor (think Chicago’s famous “Bean”) purchased the exclusive rights to its use for artistic purposes. He became the only artist in the world with access to this pigment.

As you can imagine, that did not go over well with other artists. Another British artist, Stuart Semple, responded satirically by introducing “the world’s pinkest pink,” available for a modest cost to anyone other than Anish Kapoor. Eventually, Semple would develop a black even darker than Ventablack, the “world’s mirroriest mirror chrome paint” and “the world’s most glittery glitter,” making them widely available to everyone… except Kapoor. Semple is now equal parts pigment scientist, visual and performance artist, entrepreneur, and satirist. It is a fascinating story of pigments, artistic freedom, intellectual property, and late-stage capitalism. All because of the color black.

On to Printing

This all came to mind this week as I planned the final elements for the printing of our edition of Master and Commander. As paper finally began to arrive in the print shop this week, we came tantalizingly close to starting to print.

With everything now in place, Monday will see us start to actually put ink to paper as we begin printing Master and Commander. I will, of course, provide plenty of photos and videos of the process, as well as my thoughts and meanderings as energy allows. In the meantime, I wish you all fair winds and following seas.

Cross posted to my substack!

As always, I leave more knowledgeable than when I arrived. Thank you.